In the weeks following the 2019 World Justice Forum, WJP has been pleased to highlight winning World Justice Challenge projects in turn. These winners represent the top projects in a global competition to identify, recognize, and promote good practices and successful solutions to improve access to justice. This week, we discuss insights of the "Malawi Resentencing Project" from the Cornell Centre on the Death Penalty Worldwide, The Malawi Legal Aid Bureau, and Reprieve.

Thank you to the teams at Cornell Centre on the Death Penalty Worldwide, The Malawi Legal Aid Bureau, and Reprieve for detailing the work and impact of this important project.

Can you describe the project in its most simple terms?

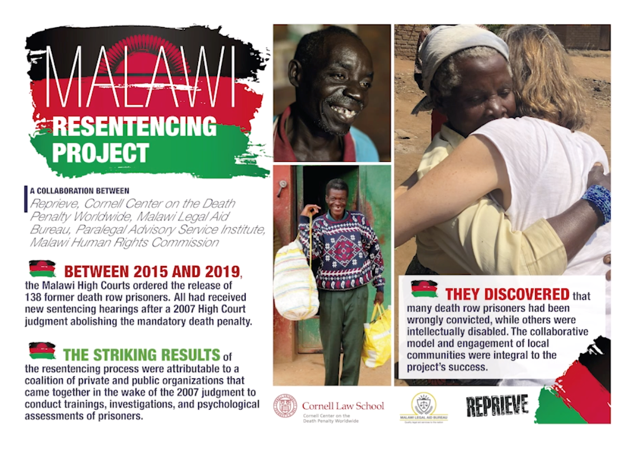

In 2007, Malawi’s High Court abolished the mandatory death penalty. In the wake of this decision, approximately 170 prisoners were entitled to seek reduced sentences based on mitigating evidence that had never before been considered by the courts. A coalition of stakeholders created the Malawi Resentencing Project to investigate and present mitigating evidence in these death penalty cases and ensure the sentencing hearings met international fair trial standards. As a result of the project, over 140 former death row prisoners have been released.

Why was this project so necessary?

As one of the poorest countries in the world, Malawi's justice system operates on a shoestring budget. It has fewer than 20 public defenders nationwide. In this context, the implementation of a 2007 High Court Judgment striking down the mandatory death penalty posed a formidable challenge. By late 2014, only a single prisoner’s case had been reviewed. The Malawi Capital Resentencing Project was launched in 2014 to address these challenges and bring justice to the men and women who had languished for years on Malawi’s death row. Without the Resentencing Project, the great majority of prisoners would have remained under sentence of death, or in prison for the rest of their natural lives.

Prior to 2007, every person convicted of homicide in Malawi was automatically sentenced to death without consideration of their life history or the circumstances of the offense. This sentencing scheme was struck down as unconstitutional by the Malawi High Court in Kafantayeni v. Attorney General. As a result of the Kafantayeni decision, every man and woman given a mandatory death sentence was entitled to a new sentencing proceeding where they could present mitigating evidence such as good character, youth, mental illness, or any other factor that diminished their moral blameworthiness. Approximately 170 prisoners were legally entitled to a new sentencing hearing under the decision. But it was a very different question as to whether and how this would happen in practice, particularly given Malawi’s under-resourced criminal justice system.

Before the Malawi Resentencing Project, Malawian lawyers lacked the training and resources to gather mitigating evidence. Mitigation investigations are critical to establish the factors that lead to the commission of an offense. In the Malawi Resentencing Project, the investigations often revealed that prisoners suffered from mental illnesses or intellectual disabilities that directly affected their actions at the time of the crime. Other times, the investigations provided critical context: for example, we discovered that one of our Resentencing Project clients had killed her husband after he attacked her and her mother. We discovered that others were juveniles at the time of the crime, but their youth had not been recognized by the courts because of the length of time they had spent awaiting trial.

Another challenge was that Malawi lacked psychiatrists qualified to conduct mental health assessments to determine whether any of the prisoners were intellectually disabled or mentally ill—conditions that would preclude the imposition of the death penalty. Through the project, we trained local mental health workers to conduct the assessments. We also utilized a basic screening tool – the Raven’s Progressive Matrices – to determine whether prisoners might have intellectual disabilities.

Can you tell us about the positive human impact the project has had?

The Malawi Resentencing Project has saved lives. It has given those formerly facing a lifetime in prison at risk of execution an opportunity to rebuild their lives. Of the 169 prisoners who were ultimately eligible for a sentence rehearing, 156 received reduced sentences. None was resentenced to death. As of May 2019, a total of 142 former death row prisoners have been released after serving their sentences.

The project has helped ensure that some of the most vulnerable people in Malawian society – prisoners and their families – receive access to the courts and the chance to re-join their communities. At the same time, it has ensured that those who are convicted of serious crimes receive sentences that are commensurate with the gravity of the offence. Not only has it saved lives, it has changed opinions on the use of the death penalty to the point where abolition is a real possibility. The Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide and the Paralegal Advisory Services Institute conducted a survey of traditional village leaders affected by the project to determine whether and how their views of capital punishment had changed. Each of the leaders presided over a village that had received a released death row prisoner. The overwhelming majority stated that the State should not use the death penalty to punish individuals convicted of murder. Many noted that rehabilitation is impossible if a prisoner is executed. As one traditional leader noted, "There is no reform in death."

The Resentencing Project did not end after the courts delivered their judgments. It worked to endure that the released prisoners received technical skills so they could integrate back into society and become productive citizens in their home communities. A key partner in this goal was The Prison Fellowship of Malawi, the country’s sole Halfway House, which enables newly released prisoners to acclimatize back into society in a supportive environment.

The project helped demonstrate that all persons—even those convicted of violent crimes—are capable of reform. One example is Byson Kaula, who spent 24 years in prison before he was released, and who now works as a volunteer with the Prison Fellowship and counsels prisoners in the same prison where he was once incarcerated. Another is Mtilosera Pindani, who was arrested at the age of 16 for killing a man who had assaulted his sister. He had been sentenced to die, but thanks to the Resentencing Project, he was released after 22 years and is now a traditional leader in his village.

Finally, the project is having an impact outside of Malawi. Kenya is now looking to Malawi as a model for a similar project relating to the application of the death penalty. Like Malawi, Kenya abolished the mandatory death penalty in 2017 and is preparing to resentence over 4,000 prisoners. The blueprint created by the Malawi Resentencing Project will guide Kenyan stakeholders to ensure that mitigating evidence is gathered and presented to the courts, and that the jurisprudence created in Malawi is available to help guide fair sentencing decisions.

What has made this project so effective?

Building a broad coalition of partners from both grass roots organizations to international NGOs was key to the success of this project. Members of the coalition included the Malawi Human Rights Commission (MHRC), Paralegal Advisory Service Institute (PASI), Centre for Human Rights Education, Advice and Assistance (CHREAA), the Legal Aid Bureau, the Director of Public Prosecutions, the judiciary, the prison service, Chancellor College, the Malawi Law Society, the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide, and Reprieve.

The Cornell Center trained paralegals and lawyers regarding the investigation and presentation of mitigating evidence. With the support of the Tilitonse Fund, lawyers and judges also received training in topics such as mental health, trauma, and fetal alcohol syndrome. Psychiatrists from the United States and South Africa trained Malawian mental health workers in the administration of a non-verbal test to screen for intellectual disability. At the same time, working with the judiciary, the project proposed creative strategies to streamline the re-sentencing process and conserve resources.

Resentencing hearings began in February 2015 and members of the coalition were involved at every stage of the process to ensure the hearings met international fair trial standards. From providing direct representation to prisoners, to assisting in the drafting of legal submissions, to providing logistical aid (including funding for travel expenses so that lawyers, prosecution and the judiciary could attend the hearings), the coalition supported and guided the process. All stakeholders involved in the project were a vital element in its success. They pulled together to organize and attend hearings, conduct mitigation investigation, obtain mental health assessments, collect records, and ensure that prisoners had enough bus fare to return to their villages after their release.

Capacity building among local organizations was another key element of the project – and essential to ensure its sustainability. The coalition included organizations such as the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide and Reprieve, who have vast experience and expertise in undertaking mitigation investigations. These organizations worked closely with the Malawi-based members of the coalition, supporting them in the investigation process, creating guides to effective legal representation, and supplying helpful precedent from international and foreign jurisdictions. Not only was this exercise essential in ensuring prisoners on death row received access to justice, but it also built capacity within Malawi’s legal civil society.

The project was truly invested in each individual it supported. It monitored and counseled each prisoner before he or she was released. It provided expenses for meals and transport to their home villages. It identified the most vulnerable prisoners and ensured they received skills training in a six-month program at the halfway house. In the months and years after each prisoner’s release, paralegals checked in on the former prisoners to ensure they were safe and healthy.

Finally, the stakeholders worked hard to secure the support of traditional leaders (who are highly respected and influential in the community) for those returning from death row. This was crucial to not only facilitate each prisoner’s rehabilitation following his or her release, but to ensure the broader community would accept the prisoner and enable his successful reintegration. Paralegals travelled to the villages of prisoners eligible for a sentence rehearing to inform villagers about the change in the law and the possibility of the prisoner’s return. This not only ensured that the community’s views were considered in each resentencing hearing, but allowed the community to prepare for the prisoner’s return to their community. Many villages prepared welcome celebrations for released prisoners, helping to lessen the stigma that each prisoner faced.

How can the approach of this project be applied in other parts of the world?

The principles and best practices developed through the Malawi Resentencing Project can be adapted to tackle a death row of any size. At the heart of this project is the principle that every person is entitled to access to justice. In order to ensure this, each case has to be examined on its own merits. The investigation techniques developed through this project can be applied to any case in any jurisdiction—even those with minimal resources. If it can be done in Malawi, it can be done anywhere. Moreover, the dozens of helpful court decisions, including progressive jurisprudence covering the mitigating weight of mental illness, intellectual disability, economic hardship, and foreign nationality (among other issues) can be applied in other retentionist countries in the region.

The collaborative aspect of the project is also replicable. The project brought together a huge array of stakeholders mentioned above, as well as international lawyers, law students from Malawi’s Chancellor College, and a host of judges, court officials, investigators, prison officials, and mental health experts, to deliver new sentence hearings to nearly 160 prisoners to date. The stakeholders met regularly to ensure buy-in to the resentencing exercise, reflect on their role in delivering it, develop strategies and processes for implementing the project, and build new knowledge, skills and capacities.

What is next for this project?

The next phase of the project is twofold: first, we will share the lessons learned from Malawi with stakeholders in Kenya and other countries that retain the death penalty. Second, we will use the lessons learned from the project to support a national dialogue in Malawi regarding abolition of the death penalty.

As noted above, in December 2017 Kenya’s Supreme Court struck down the mandatory death penalty. Members of the coalition who were involved in the Malawi Resentencing Project have been working closely with the Kenyan Taskforce on Resentencing to replicate the success in Malawi. Moreover, neighboring Tanzania may also abolish the mandatory death penalty. Tanzania, which shares a common border and many of the same legal challenges as Malawi, is perfectly situated to benefit from the Malawian legal community’s expertise.

To date, the project has contributed to the government’s softening approach towards the death penalty and indirectly contributed to Malawi’s first vote in favor of the UN resolution calling for a global moratorium on the application of the death penalty on 19 December 2016. The survey of traditional leaders has shown that public support for the death penalty is weak. The groundwork laid through the resentencing project has created a favorable environment for Malawi to achieve abolition.

Finally, all those involved in the Project will continue to support and facilitate the sentence rehearings of the prisoners who are still incarcerated. Approximately ten persons are awaiting the results of a Supreme Court decision that will determine their entitlement to a sentencing hearing. We are hopeful that the court will rule in their favor. Depending on the availability of resources, we will also continue to support those who have been released or are due for release under the project, by ensuring they have the support they need in order to successfully reintegrate back into their communities.

How has the World Justice Forum and winning the World Justice Challenge helped your work?

Recognition of the project at the World Justice Forum has been incredibly valuable. We were able to share the success of the Malawi Capital Resentencing Project on an international stage – something that would not have happened without the Forum. It provided a valuable networking opportunity for the representatives of the Malawi Resentencing Project at the Forum to meet and speak with funders and others working in the criminal justice sector. Winning the World Justice Challenge has enhanced the profile of all the stakeholders involved in the project.

The prize money will also have a large impact on the project. The coalition of organizations involved in the Project have decided that the money should be spent on facilitating the sentence rehearings of the ten prisoners who are still awaiting their day in court. This will ensure that each remaining prisoner will receive access to justice, despite ongoing resource constraints.

Is there anything else you want to add?

We are incredibly grateful that the Malawi Resentencing Project was chosen to be recognized at the World Justice Forum and selected as a winner of the World Justice Challenge and we thank you for all your support.

Learn more about the World Justice Challenge and all 30 finalists here, and watch the 2019 World Justice Challenge awards and more videos from the World Justice Forum: Realizing Justice for All here.