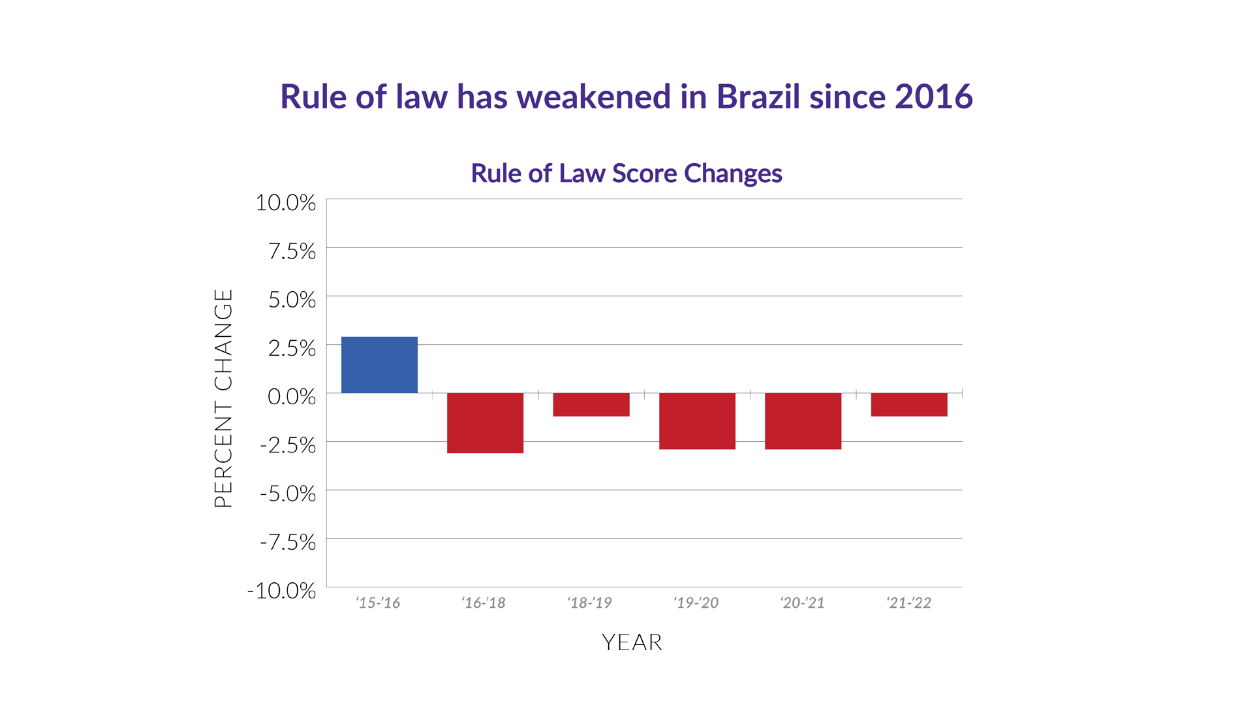

Brazil has experienced one of the world’s largest declines in rule of law since 2016, with its overall rule of law score falling each year for five consecutive years, according to data from the 2022 World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index. These declines come amidst a five-year trend of global backsliding. In Brazil, as globally, the declines have been largely driven by rising authoritarianism, exhibited by weakened constraints on government powers and the deterioration of fundamental rights and freedoms. The falling effectiveness of the civil justice system, exacerbated by COVID pressures, has been another major driver of declines.

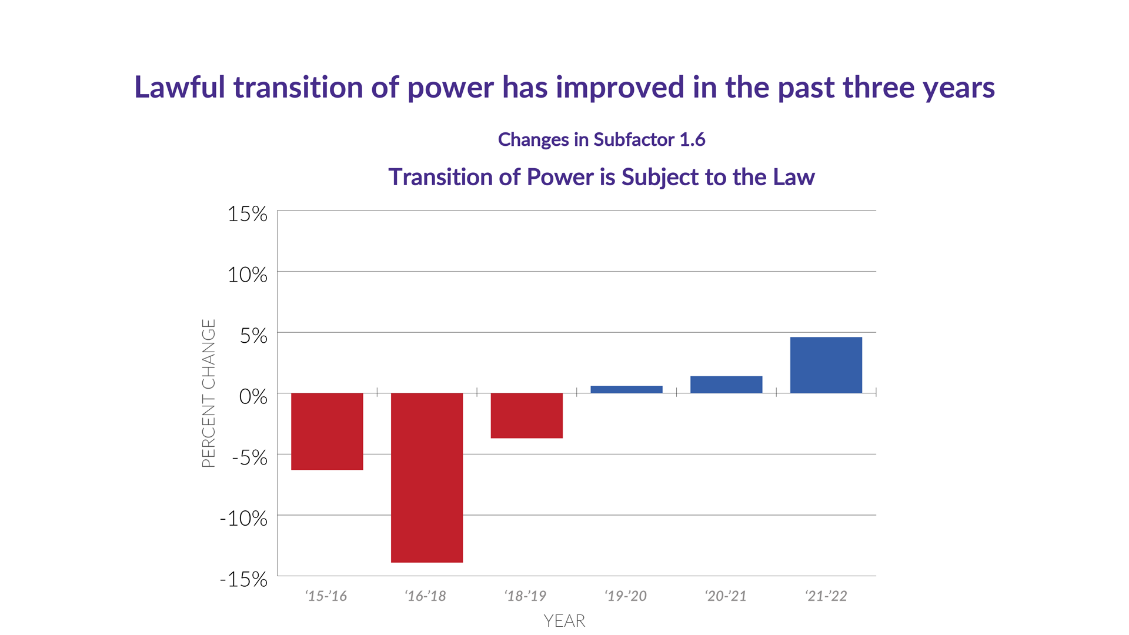

Conversely, an area where Brazil has shown an improvement over the last several years is whether the transition of power is subject to the law. Among other things, this Index subfactor measures confidence in elections and access to the ballot. The 2022 data – which was collected prior to October’s national election – shows that lawful transition over power has improved.

These challenges and opportunities were the focus of a recent discussion hosted by the WJP and FGV Rio de Janeiro Law School that brought together experts from the academic, legal, financial, and business communities in Brazil. The discussion was moderated by WJP board member and former president of Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court, Ellen Gracie Northfleet. During the panel discussion, WJP Chief Research Officer Alejandro Ponce briefed attendees on this year’s WJP Rule of Law Index, including Brazil-specific data.

“In general, when countries experience a decline, it tends to be larger in magnitude than when they improve,” Ponce told the panel.

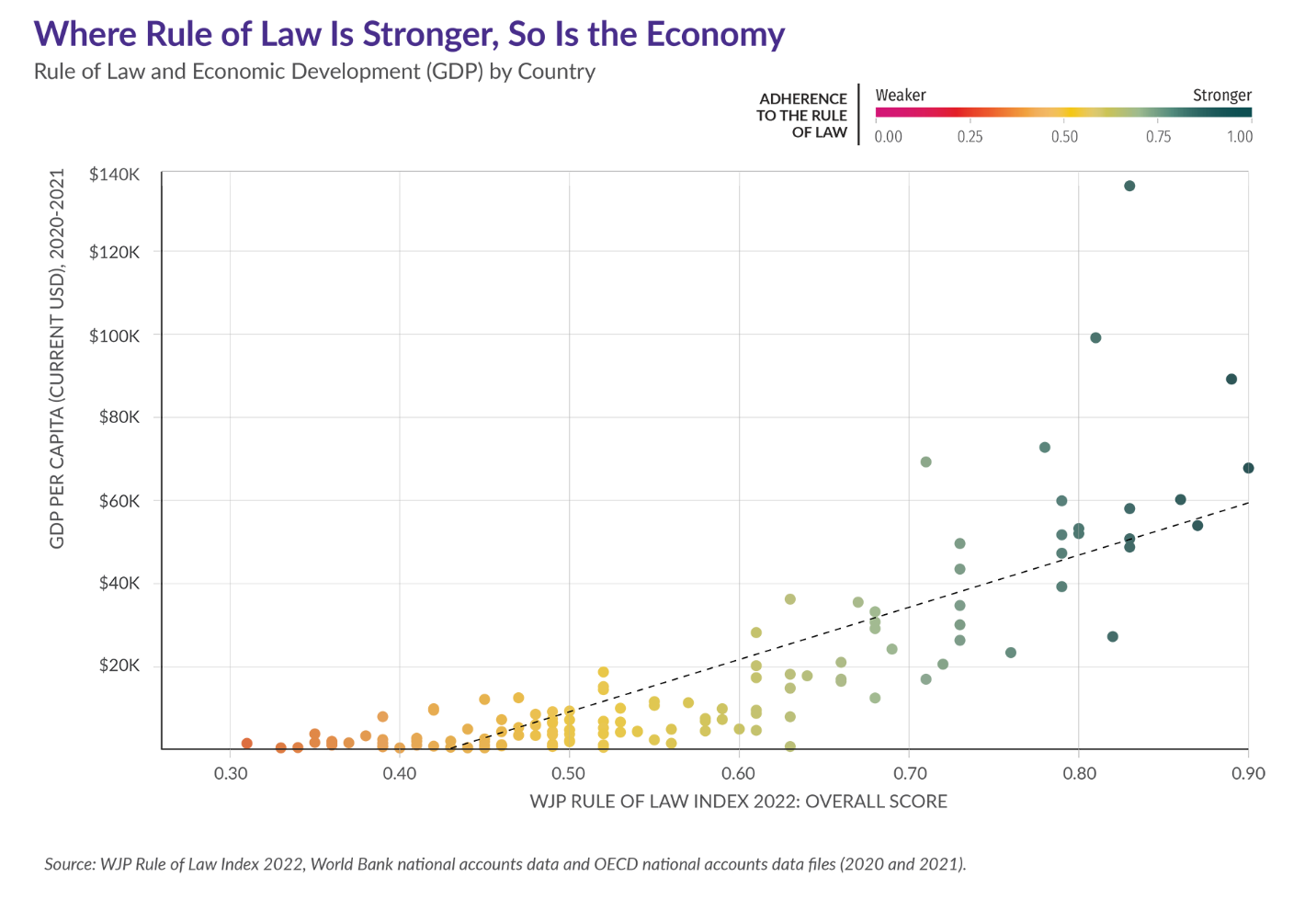

This graph sparked further discussion among the panelists about how the rule of law affects all aspects of Brazilian society and how the Index can be used as a tool to improve the rule of law.

Speaking about how economic stability is tied to the rule of law, Joaquim Falcão of the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI), noted “there is a strong correlation between wealth, both at the personal individual level and country level, and the implementation and enforcement of the rule of law. No country or region can escape this fact.”

“I also think that in regions where the rule of law is enforced, people are happier,” Armando Castelar, associate researcher at FGV’s Institute of Economics added. “There must be a strong correlation between rule of law and happiness. But what comes first? The rule of law, then increased per capita income and happiness? Or do we need to have well-paid people who are happy to have the rule of law?”

In addition to the economic implications of the rule of law, the Brazilian judicial system was also a topic of discussion.

Renata Gil, president of the Association of Brazilian Magistrates, noted she understands the challenges facing the country’s civil justice system, but pointed out that some of these challenges come from the sheer size of the justice system. According to Gil, last year, more than 78 million lawsuits were filed in Brazil. She believes increasing the number of judges will help speed up legal proceedings.

“You can only fight inefficiency by becoming efficient,” Gil said. “We are also in need of more technological resources to decrease the perception that it takes a very long time for lawsuits to be finalized in the Brazilian justice system.”

Gil proudly told the audience that Brazil’s justice system did not stop working during the height of the pandemic.

The panel all agreed that the incoming Lula administration offers an important opportunity to address the rule of law challenges in Brazil. WJP research shows that government transitions can lead to improvements in the rule of law.

“Three of the top 5 improvers in the Index this year are countries that had a recent change in administration [Honduras, United States and Belize],” Ponce told the panel. “We can see changes in the rule of law in a short period of time when there is political momentum to carry out certain things.”

Other panelists included Isaac Sidney, president of the Brazilian Federation of Banks (FEBRABAN) and Rafael Cervone, president of the Center of Industries of the State of São Paulo (CIESP).

Watch the full discussion: