For laborers around the world, the rule of law provides an important foundation for opportunity and well-being. It creates the environment by which their rights to organize and bargain collectively are protected; it shields them from discrimination; it provides a regulatory framework for workplace safety and mechanisms for resolving workplace disputes and harms. Research also shows that rule of law correlates positively to economic growth, improved health outcomes, less inequality, and higher levels of education.1 Yet workers face increasingly tough conditions for asserting their rights, especially as COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc across many vulnerable economic and demographic sectors.

Defining the rule of law and measuring how it is experienced in concrete ways matters because the rule of law is not only a public good in itself but also instrumental to a series of other public goods, including safe working conditions that align with international standards and best practices.

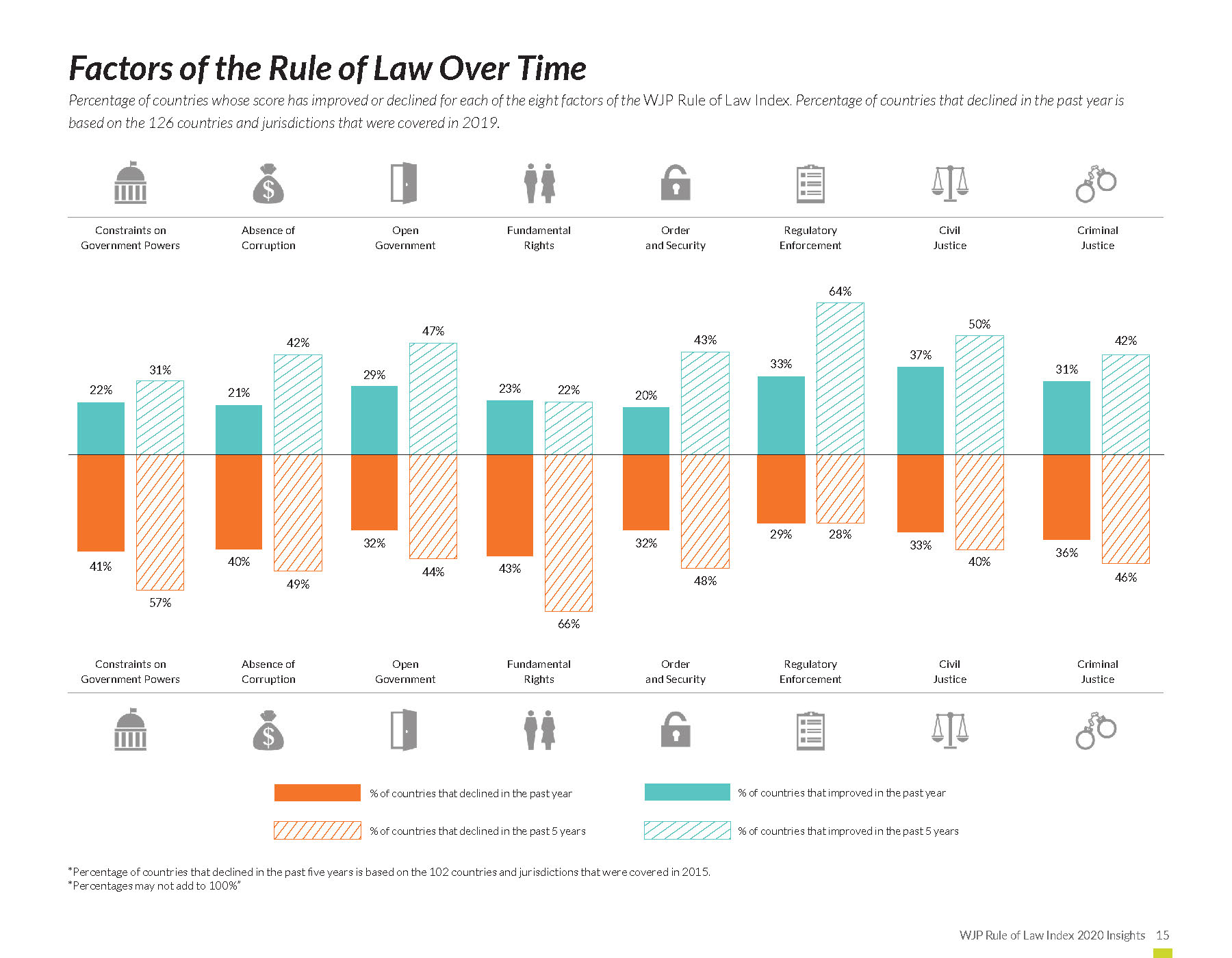

For the third year in a row, the 2020 World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index®—which measures the rule of law worldwide based on in-country household and expert surveys—reported more countries’ rule of law scores declining than improving.2 We see this trend in established democracies as well as in less free states and in every region of the world. The persistent decline is particularly pronounced in the areas of government accountability, fundamental rights, and corruption. For example, more countries have declined in their fundamental rights score than any other rule of law factor, both over the last year and the last five years.

The State of Labor Rights before Covid-19

In the area of labor rights, there is a more mixed picture. According to the data collected for the 2020 Index by the World Justice Project, slightly more countries improved than declined in their scores on the effective enforcement of fundamental labor rights. The questions covered in this survey include freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the absence of discrimination with respect to employment, and freedom from forced labor and child labor (Index subfactor 4.8).3

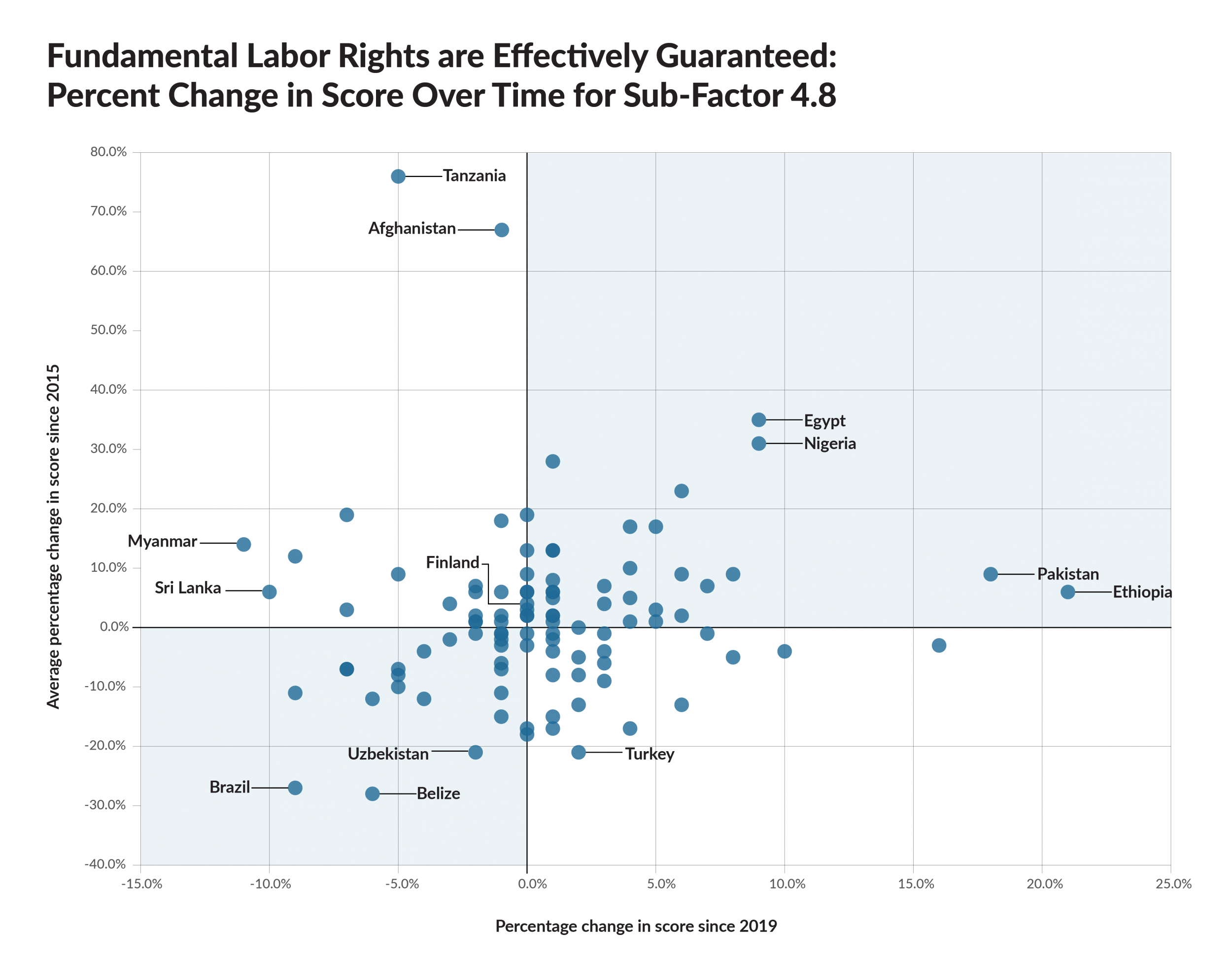

Over the most recent five-year period of data collected by WJP, the number of countries that improved or decreased on this subfactor is about the same, with 53% increasing and 42% decreasing, and around 5% not seeing significant changes. When analyzed on a population-weighted basis, the improving group of 54 countries represents 64% of the world’s population, while the declining group of 43 countries represents only 23% of the world’s population. In other words, during that five-year period, labor rights generally improved for more people around the globe.

A closer look at the numbers underscores a mixed picture of both progress and regression. On the positive side, historically weaker rule of law countries have seen significant improvements in their labor rights score. However, many of these countries have labor rights scores that fall far below the global average (e.g., Tanzania, Afghanistan, Egypt), indicating that while improvements have been seen over the last few years, countries are still struggling to adequately protect and uphold labor rights. On the other hand, some weaker rule of law countries have also seen large declines on labor rights (e.g., Belize, Brazil, Turkey), proving again that there is no clear, one-size-fits-all picture regarding labor rights and its correlation to rule of law performance more broadly.

More solid rule of law societies, with the notable exception of the United States, have had higher and more stable scores specifically on labor rights (with most of Europe, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and Uruguay near the top). Even in a better scoring region such as Europe, however, we see declines over the last five years in Croatia (-11%), the United Kingdom (-8%), Sweden (-8%), and Bulgaria (-7%), while improvements were registered in lower ranked Serbia (+28%), North Macedonia (+9%), and Romania (+7%).

COVID-19 has made a weak labor rights situation more challenging

Since WJP released its Index data in March 2020, reports from around the world suggest the general condition of fundamental rights and the rule of law has deteriorated markedly. The burden of the coronavirus has fallen especially hard on workers in the health and elder care sectors, some of whom faced extraordinary risks to continue providing life-saving treatment to patients sick with COVID-19. The imposition of lockdowns and quarantines has hit the restaurant, travel, and entertainment industries badly, with millions laid off and unable to find new work. Many migrant laborers, especially in the agricultural sector, were unable to travel to their usual fields of work or were forced to return home under strenuous circumstances, as notably occurred in India. With the closure of schools and child care facilities, women across multiple arenas of work had few options but to reduce or eliminate their paid labor as they picked up the slack on unpaid household duties. Women were also more likely to be at risk of infection due to their work in front-line service jobs, and more vulnerable to inadequate medical care as informal workers.

In addition to the direct effects of the pandemic on employment, some governments took advantage of the crisis to repress freedom of expression, information, and assembly, rights essential to protesting poor working conditions. According to recent analysis by Freedom House and the University of Gothenberg’s Varieties of Democracy project, freedoms of expression, association and the media have all suffered in the last year. A particularly pernicious inequity has arisen against health workers who already face dire risks by virtue of their occupations caring for others in hospitals and nursing homes. In a few countries, such as Egypt and Nicaragua, health workers have faced arrest or administrative punishments on charges of allegedly “spreading false news” when they have publicly criticized their government’s handling of the pandemic. Amnesty International reported attacks or threats against healthcare workers by 31 governments including in Malaysia, and cases of doctors and nurses in Russia and the United States being fired or charged after complaining of lack of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Some signs of hope

Unions, NGOs, journalists, and citizens have responded bravely to the unfolding pandemic crisis through both direct humanitarian assistance and other services to victims. WJP’s World Justice Challenge 2021, a global competition to recognize innovative projects responding to the rule of law challenges posed by the pandemic, has identified a number of inspiring examples of direct support to workers affected by the crisis. In Kenya, the Dhobi Women Network launched the Inua Mama Fua project to provide food, PPE, psychosocial and access to justice services for women domestic workers in Nairobi who are currently unable to fend for themselves due to the ongoing pandemic that saw their employers send them home. The Guatemalan Women’s Association in Spain pursued strategic litigation and other legal tools to protect migrant workers’ ability to work and receive social benefits during the pandemic. In Nepal, in response to the heightened vulnerabilities of migrant laborers, People Forum provided free legal aid to victims, prepared policy papers, and recommended repatriation and reintegration of returning migrant workers.4

In sum, the COVID-19 crisis has eroded the rule of law environment for laborers around the world. While WJP’s data revealed some positive trends before the pandemic struck, the corona-crisis has had mostly negative consequences for the labor rights movement. In response, societies are beginning to acknowledge the deep structural inequities of current economic and rule of law conditions for most workers. The next WJP Rule of Law Index, to be released by October of 2021, will provide additional data to help inform unions, activists, governments and the private sector on what priorities need attention and resources as we build a more just recovery from the pandemic.

1 According to WJP 2019 Index data mapped against World Bank data, the CIA World Factbook, and the Vision of Humanity Global Peace Index 2019. Graphs of these correlations can be explored here.

2 The World Justice Project, 2020 WJP Rule of Law Index®, 11 March 2020. Most of the data for the 2020 Index was collected in the second half of 2019.

3 You can learn more about questions included in WJP’s GPP and QRQ questionnaires here.

4 You can explore more innovative solutions to challenges posed by the pandemic in areas of access to justice, fundamental rights, anti-corruption efforts, and accountable governance through the World Justice Challenge 2021 website.