The Rule of Law in Hungary

In the first weeks of 2019, opposition parties, unions, and thousands of citizens in Hungary united in renewed protest against the two latest reforms by Prime Minister Viktor Orban and the Fidesz party. The first reform approves the creation of a parallel court system that will be staffed with judges selected by Orban's justice minister. The second reform allows companies in Hungary to require employees to work up to 400 hours of overtime a year and to delay overtime payment for up to three years.

Protests against these reforms highlight the increasing dissatisfaction Hungarians feel toward the government's dismantling of rule of law protections, particularly regarding the independence of the judiciary and fundamental rights. World Justice Project's (WJP) annual WJP Rule of Law Index provides data on citizens' perceptions of both protections, as well as a picture of the overall status of the rule of law in Hungary.

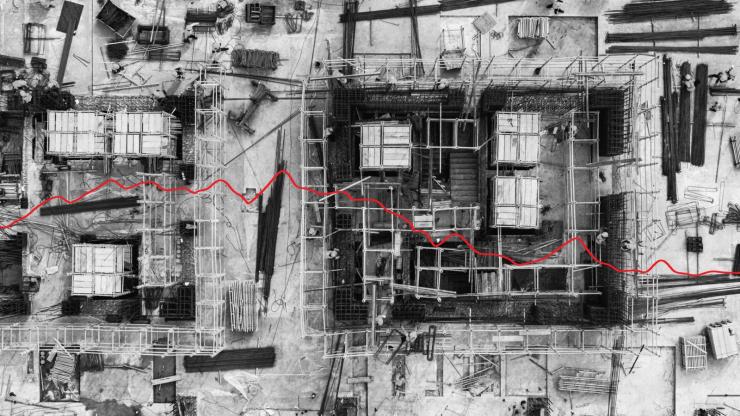

The Index measures rule of law performance across 8 factors and 44 sub-factors in 113 countries. Country scores are scaled from 0.00 to 1.00, with 1.00 representing the strongest adherence to the rule of law. Hungary's overall WJP Rule of Law Index score is 0.55—placing it 50th out of the 113 countries measured in 2017-2018. Within the EU, EFTA, and North American region, Hungary's overall score ranks 23rd out of 24 countries.

Constraints on Government Powers in Hungary

The data indicate that Hungarians see weaknesses in government accountability and sanctions for official misconduct. On Factor 1 of the WJP Rule of Law Index, which measures how effectively institutions constrain government power, the country ranks 93rd out of 113 countries and 24th out of the 24 countries in its region. (See chart: "Factor 1: Constraints on Government Powers")

Moreover, pressure on the rule of law by Fidesz is likely to increase. Fidesz's two-thirds majority in Parliament has allowed it to pass legislative reforms unabated, including the two recent laws which threaten judicial independence and fundamental rights.

Judicial Independence

The first reform which reflects this increased pressure on the rule of law is aimed at the judiciary, an important institution for limiting government abuses of power. The new administrative courts will allow Fidesz to acquire jurisdiction over electoral law, political protest, and public corruption via a parallel system, effectively stripping the judiciary of its oversight functions.

According to data from the WJP Rule of Law Index 2017-2018, Hungarians are already concerned about judicial independence, as measured by sub-factor 1.2. Hungary ranks 23rd out of 24 countries within the EU, EFTA, and North America region. (See chart: "Sub-Factor 1.2: Government Powers are Effectively Limited by the Judiciary")

Protests against Hungary's new court system show the low confidence Hungarians have in the ability of the judiciary to do its work in an impartial and independent manner.

Fundamental Rights: Labor Law Protections

The second reform allows businesses to demand overtime work and to delay payment for this work for up to three years, a concerning development for the protection of fundamental labor rights. WJP data shows that Hungarians already feel their fundamental rights are threatened: in the WJP Rule of Law Index 2017-2018 Hungary is ranked second to last in its region on Factor 4: Fundamental Rights. (See chart: "Factor 4: Fundamental Rights")

Despite a low Factor 4 score, sub-factor data show that labor rights protections have been perceived as one of the strongest components of Hungary’s rule of law. Hungary’s score on sub-factor 4.8, which measures the protection of labor rights, is 0.70, one of the country’s five highest sub-factor scores.

Professor Tamás Gyulavári, head of the Labor Law Department at Pazmany Peter Catholic University in Budapest, told the WJP that through the labor rights reform “the basic function of protecting the health of employees is not fulfilled by the new rules on working time,” and that the reform only serves to solve Hungary’s labor force shortage in the short term. Instead, Professor Gyulavári notes that “active labor market programs (i.e, training, retraining, etc) should be launched to tackle labor shortage in the long run,” in addition to exploring motorization, digitalization, and the raising of wages to stifle Hungary’s brain drain. In light of the harsh labor law reform and subsequent protests, WJP's data on Hungarians' perceptions of labor rights protections may explain why this labor law reform has become a unifier for opposition parties and citizens.