The World Justice Project is launching a multidisciplinary initiative to expand knowledge of the relationship between public health and the rule of law, and to identify measures to tackle the twin crises of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rule of law where they intersect.

This essay provides an introduction and first step toward building a research agenda, sharing knowledge, and supporting efforts to recover and rebuild effective governance founded on the rule of law. Download the full introduction essay and browse additional policy brief installments at the end of this post.

The COVID-19 pandemic strikes in the midst of a mounting global rule of law crisis in which respect for key principles of good governance has been eroding in many countries for a number of years. This new pressure on the rule of law and its risk of further erosion makes the pandemic particularly dangerous. At the same time, gaps in the rule of law risk worsening the COVID-19 crisis and undermining our ability to respond effectively.

The rule of law is a durable system of laws, institutions, norms, and community commitment that delivers accountability of both government and private actors, just laws that protect fundamental rights, open government, and accessible justice. In strong rule of law societies, these four principles intersect to ensure citizens have effective, transparent, and accountable institutions that can defend liberty, provide for public safety, including public health, and facilitate prosperity.

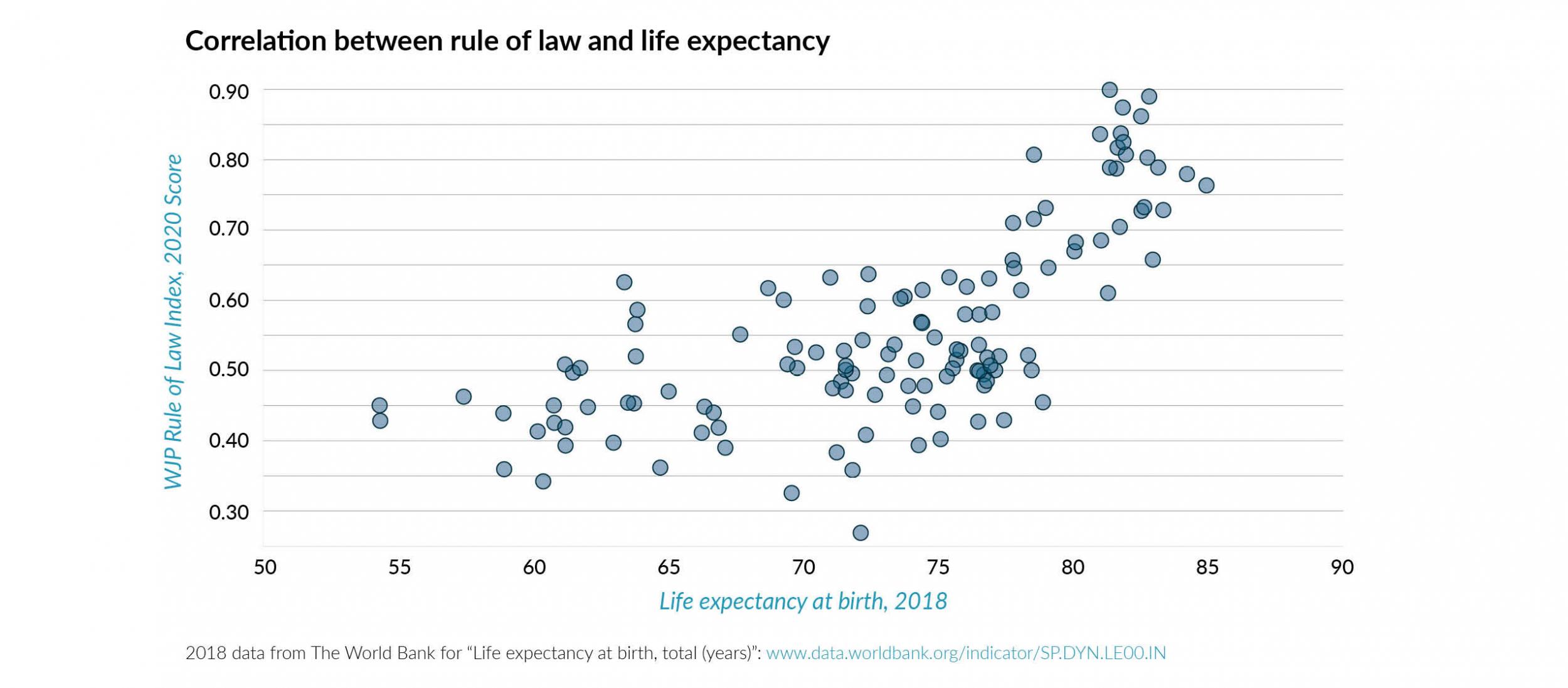

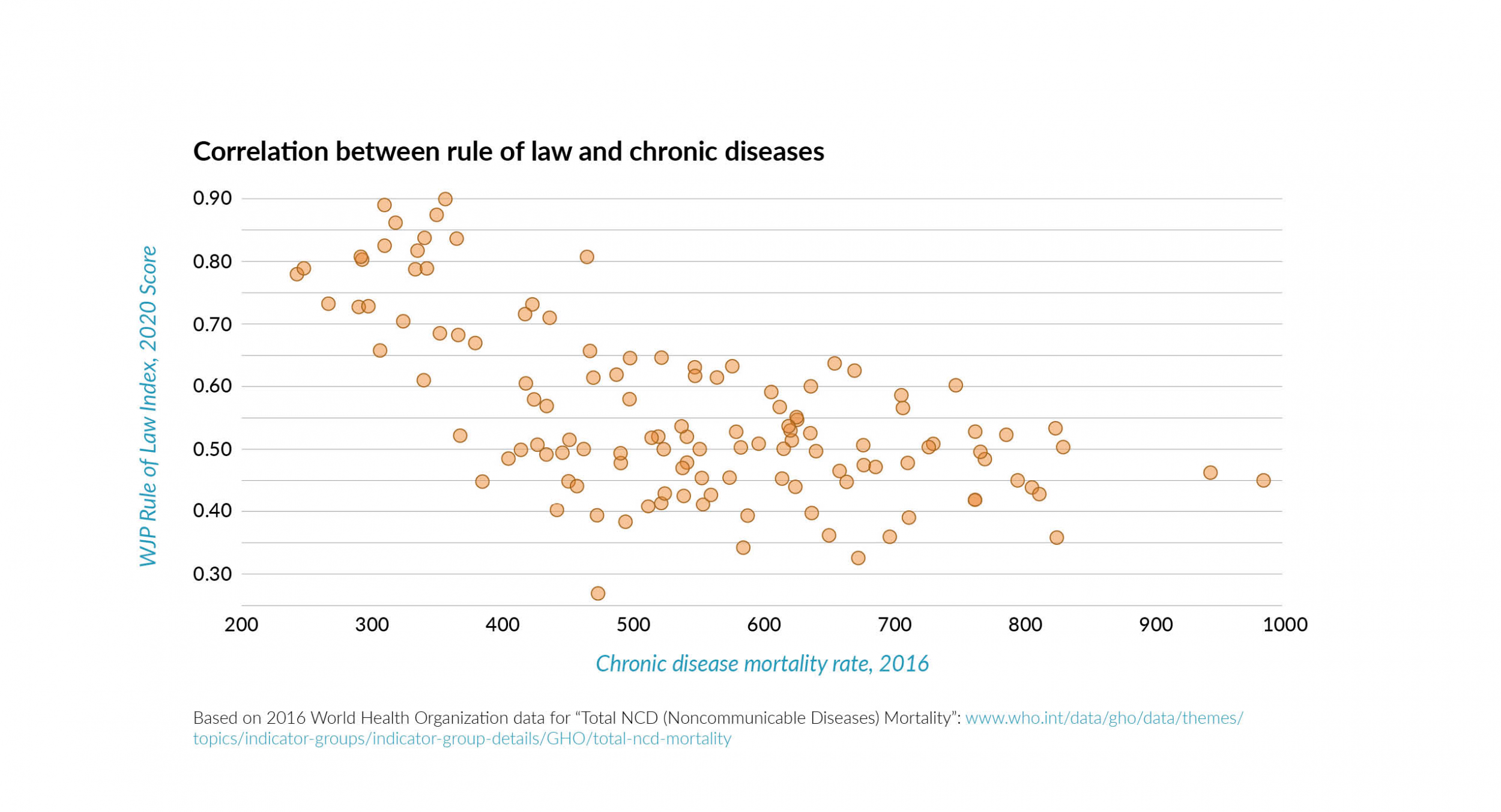

Evidence suggests a positive correlation between rule of law and public health—countries with better rule of law enjoy lower rates of maternal and infant mortality, longer life expectancy, and lower incidence of chronic diseases.1 The rule of law nurtures trust in institutions and underpins a social contract among citizens, both indispensable to solving a public health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic in which a collective approach is the only way to contain and control the disease.

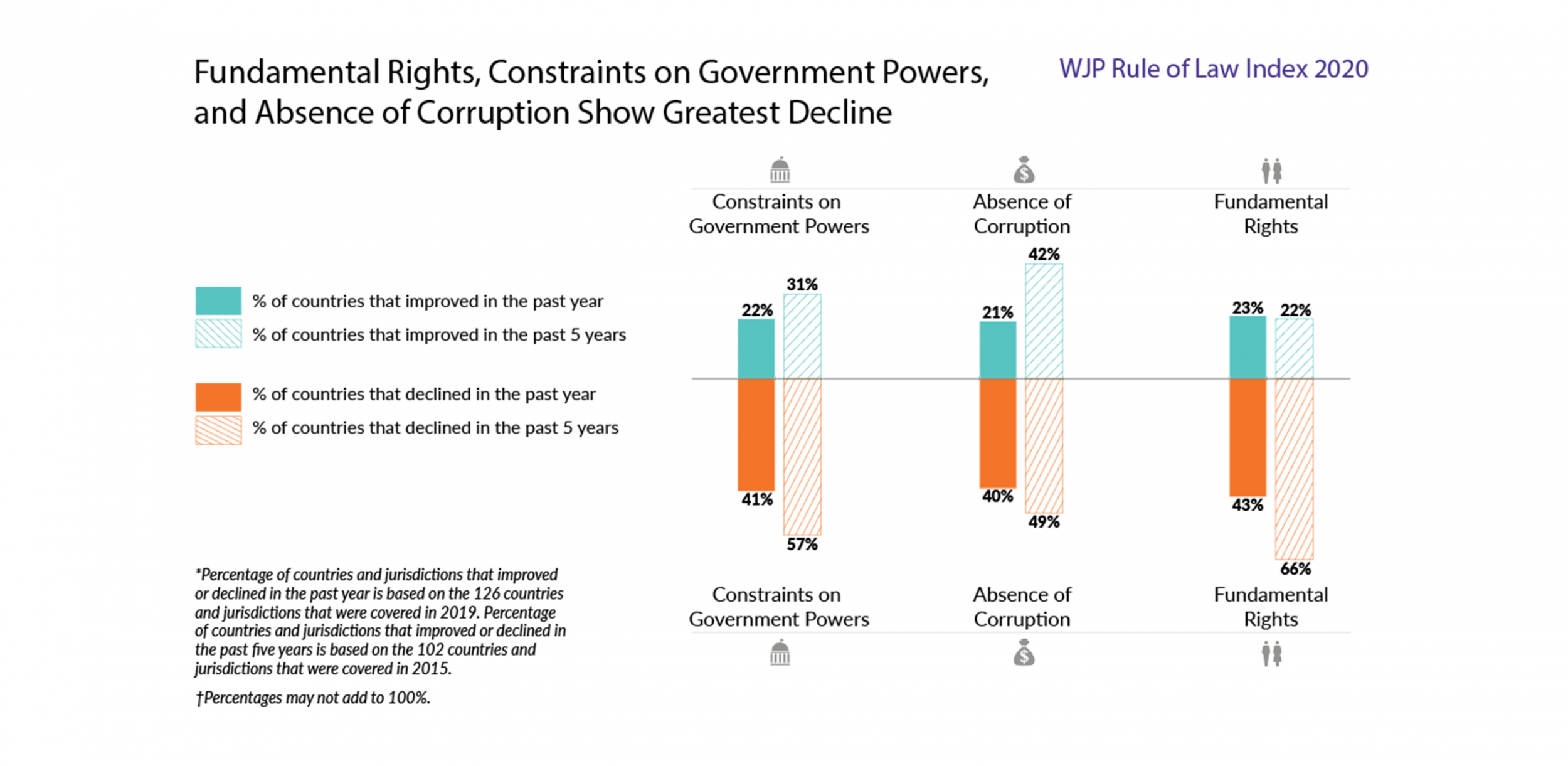

Unfortunately, evidence continues to mount that just when our societies need strong rule of law to respond effectively to the pandemic, these critical norms of good governance, and the capacity of states to deliver them, are deteriorating around the world. For the third year in a row, the recently published 2020 WJP Rule of Law Index® reported more countries’ rule of law scores declining than improving.2 We see the trend in established democracies as well as in less free states and in every region of the world.

The persistent decline is particularly pronounced in the Index factors that measure “Constraints on Government Powers,” “Fundamental Rights,” and “Absence of Corruption,” three areas especially susceptible to erosion during emergencies. Together with “Access to Justice”—another area of weakness for the rule of law in many countries—WJP’s initiative will focus on understanding the relationship between these four aspects of the rule of law and public health and identifying measures that can be effective in strengthening both.

Constraints on Government Powers

The COVID-19 pandemic seriously risks further erosion of constraints on government powers, as leaders with an authoritarian bent amass new powers through emergency measures, and courts, legislatures, and other institutional and citizen checks are hampered in carrying out their constitutional duties and rights. Elections to hold political leaders accountable are being postponed indefinitely or held without proper public health precautions, harming citizens’ rights to be heard.

Fundamental Rights

Fundamental rights are threatened when new emergency laws and decrees criminalizing the spreading of misinformation about the virus or censoring reports about government missteps are used to silence or attack journalists and opposition critics. Good public health practice to control epidemics calls for tracking how the virus spreads, to whom, and how quickly. But ubiquitous tracking devices like mobile phones can also become easy entry points for violating rights to privacy, particularly against a regime’s political opponents. Striking evidence has emerged of discriminatory enforcement of lockdown measures and curfews against people on the basis of ethnicity, race, religion, and gender identity.3

Corruption

Public health emergencies are rife with risk of corruption. Even without a pandemic, the health sector has a serious corruption problem. In a 2019 report, Transparency International estimated that corruption in the health sector costs $500 billion per year globally.4 The pandemic threatens to compound this problem as governments rush supplies and resources to those in need, shortcutting procedures designed to prevent waste and fraud. Shortages create opportunities for price-gouging, scams involving the sale of defective or counterfeit goods, and bribery. Meanwhile, audit agencies, potential whistleblowers, and other oversight mechanisms are hampered by the virus in their ability to provide much-needed checks on the use of public health resources.

Access to Justice

Further, the health crisis highlights and reinforces serious gaps in access to justice, particularly for marginalized communities. The World Justice Project has estimated that 5 billion people globally have unmet justice needs.5 This global justice gap includes 2.1 billion people employed in the informal economy, 2.3 billion who lack proof of housing or land tenure, and 1.4 billion people who have unmet civil or administrative justice needs—people who have been unable to resolve everyday legal problems such as issues relating to land, housing, or employment; family disputes; debt or consumer issues.6 The severe economic fallout of the pandemic is generating even more justice needs, particularly among poor and marginalized communities, many of whom lack legal identity, housing, or formal employment and therefore may not be able to access emergency assistance. Meanwhile, chronically under-resourced justice institutions, many of them operating at reduced capacity due to the pandemic, risk falling even further behind.

While the pandemic risks worsening the rule of law in each of the ways outlined above, these gaps in the rule of law also threaten societies’ ability to respond effectively to the pandemic, exacerbating its short- and long-term effects, particularly for marginalized and vulnerable populations. Weak rule of law undermines the trust in institutions and leaders that is so critical to mounting a coordinated and effective society-wide response to the pandemic. Timely, accurate, and trustworthy information is essential to an effective response, yet governments that restrict access to information and free expression or that otherwise thwart checks on authority may not be reliable sources of such information.

Chinese authorities’ suppression of vital information about the disease, to give one trenchant example, delayed key actions that could have saved thousands of lives. Beyond China, leaders in many jurisdictions have downplayed the virus, obscured case numbers, or misrepresented the success of their pandemic response efforts for short-term political gain. Where leaders have talked frankly about the onerous measures needed to keep people safe, as in New Zealand, the contagion has demonstrably slowed.

Discrimination in housing, labor markets, the criminal justice system, and access to health care fuel the pandemic and complicate mitigation efforts. Minorities and women, for example, are more likely to work in low-wage “essential” jobs in groceries, public transport, trucking and delivery, and health care, where they risk greater exposure to the virus; they also tend to live in more crowded and substandard housing where transmission risks are higher. Fraud interferes with delivery of desperately needed medical supplies and services, while systemic corruption depletes resources needed for economic recovery.

Moreover, the speed of the response, combined with a debilitated legislative and watchdog infrastructure, likely will impair the ability of public health services to spend wisely and effectively.

In sum, based on evidence to date, the global pandemic reinforces worrisome trends regarding fundamental rule of law principles which, in turn, makes overcoming the crisis even more difficult. At the intersection of these twin crises of public health and rule of law stand four main concerns: constraints on government powers, fundamental rights and discrimination, corruption, and access to justice.

But the pandemic also presents a unique opportunity to catalyze reforms that will help rebuild the trust that citizens must have for good governance to function effectively, particularly in areas essential to fighting the pandemic and protecting public health over the long term. In this way, strengthening the rule of law is a critical building block for a healthy society and deserves priority attention and resources throughout the recovery and rebuilding phases to come.

In the coming weeks, WJP will be sharing with our community our latest analysis and recommendations for how to ensure that, as our societies recover from this unprecedented global pandemic, we rebuild the fundamental rule of law pillars needed for all communities to thrive. Download the this essay introduction below and keep an eye on worldjusticeproject.org/news for future installments.

Corruption and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Accountable Governance and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Fundamental Rights and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Global Justice Gap

1 Angela Maria Pinzon-Rondon, Amir Attaran, Juan Carlos Botero, & Angela Maria Ruiz-Sternberg, “Association of Rule of Law and Health Outcomes: An Ecological Study,” BMJ Open 2015;5:e007004 https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/10/e007004

2 The World Justice Project, 2020 WJP Rule of Law Index®, 11 March 2020 https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data/wjp-rule-law-index-2020

3 See Victor Madrigal-Borloz, “‘States must include LGBT community in COVID-19 response’: The how and why from a UN expert,” OHCHR, 17 May 2020, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25889&LangID=E; Human Rights Watch, “China: Covid-19 Discrimination Against Africans,” Human Rights Watch. 5 May 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/05/china-covid-19-discrimination-against-africans; Amnesty International, “Global: Ignored by COVID-19 Responses, Refugees Face Starvation.” Amnesty International, 13 May 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/05/refugees-and-migrants-being-forgotten-in-covid19-crisis-response/; Lee, Jonathan. “Police Are Using the COVID-19 Pandemic as an Excuse to Abuse Roma.” Coronavirus Pandemic | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 14 May 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/police-covid-19-pandemic-excuse-abuse-roma-200511134616420.html

4 Transparency International, “The Ignored Pandemic: How Corruption in Health Care Delivery Threatens Universal Health Coverage,” p.1 2019. http://ti-health.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/IgnoredPandemic-WEB-v2.pdf

5 Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just, and Inclusive Societies, Justice for All: Final Report of the Task Force on Justice, April 2020.

https://bf889554-6857-4cfe-8d55-8770007b8841.filesusr.com/ugd/90b3d6_746fc8e4f9404abeb994928d3fe85c9e.pdf

6 World Justice Project. Measuring the Justice Gap: A People-Centered Assessment of Unmet Justice Needs Around the World, 2019. https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data/access-justice/measuring-justice-gap