In the weeks following the 2019 World Justice Forum, WJP has been pleased to highlight winning World Justice Challenge projects in turn. These project spotlights provide insight into access to justice needs being filled, project impacts, and how successes may be replicated in other parts of the world. This week, we discuss Nazdeek's "Monitoring Maternal Health Entitlements & Increasing Access to Grievance Redressal" project, assisting women in Assam, India, to seek redressal for their maternal and child health problems.

Thank you to Shreya Sen, Senior Program Officer, and Tripti Poddar, Justice Program Associate, for speaking with us about Nazdeek's work.

Can you describe the project in its most simple terms?

The project aims to bridge the gap between marginalized communities and government officials. With a strategic approach of building legal capacity, the project empowers women from tea plantations in the state of Assam, India, to demand accountability from their government and enforce legal compliance within their work space. The first step in setting up the forum was to engage with women through community meetings and legal empowerment trainings. Through these, women workers learned to identify rights violations, record them systematically, analyze patterns of violations that emerged and then present this analysis to government officials in the forums. The process created an important shift in the community's identity from "beneficiaries" of government charity to "rights holders." It was the empowering recognition that it is your Constitutional right to engage directly with your government that led to the community owning and driving the process themselves. The project has been implemented in partnership with local organizations like Promotion & Advancement of Justice Harmony and Rights of Adivasi (PAJHRA) and indigenous women's collectives like All Adivasi Womens' Association of Assam (AAWAA).

Why was this project so necessary?

For about 2 centuries, indigenous workers in Assam's tea plantations, have lived in a state of abject poverty, isolation, and deprivation due to inadequate access to services and facilities guaranteed to them by law. Their interaction with the outside world is heavily restricted and monitored by tea management. If they protest or agitate, they face heavy retaliation. Workers lack access to the most basic facilities like toilets, creches, food grains, safety gears, medical care and so on. High levels of malnutrition and anemia in women, and low levels of literacy are rampant. At the core of all the problems faced by women in tea plantations is that they get an illegally low wage of about 2 dollars a day. In other words, workers struggle with everyday needs and survival. This is a context where a disempowered, disenfranchised community of impoverished workers is up against an exploitative, muscle-flexing industry. The community of workers is heavily dependent on the government for basic services, but their isolation is so acute that they do not know about their basic rights and entitlements, or how to access them. In this context, it became essential to innovate and think of a project that closes the large gap between a marginalized community and the systems of justice and governance meant to protect their rights.

Can you tell us about the positive human impact the project has had?

The rights-based work in developing grievance forums for community monitoring have resulted in positive impact by informing communities about various rights and entitlements, especially on maternal and child health. The interface provided by the project between the communities and government officials has allowed development of knowledge repositories as a means of seeking accountability. It has allowed for strategic advocacy work and has helped communities engage deeper with the government system at different levels, making the legal and administrative process less intimidating, by empowering communities to seek accountability on maternal health concerns at points of contention. Policy level implementation concerns have been identified, which has brought about awareness and developed a consciousness at the government level for grassroots implementation of various schemes and entitlements. Take for example, Cecilia, an indigenous female activist who we trained and have worked with for over 3 years. In one of Nazdeek’s trainings, she learned about the subsidized food that her community is entitled to receive from the government. She passed on this information to the larger community through meetings, where everyone realized that the subsidies were not being received due to corruption and red tape at higher levels of the government. She then approached the relevant local authority and demanded that they attend a grievance forum in the community. The forum was attended by over 100 women, mobilized by Cecelia, who were able to use rights-based language to place their complaints and get their subsidized food entitlement. Women like Cecilia pose an important challenge to the patriarchal status quo, and with each win, the community and the local government recognize such trained paralegals as leaders to be reckoned with.

What has made this project so effective?

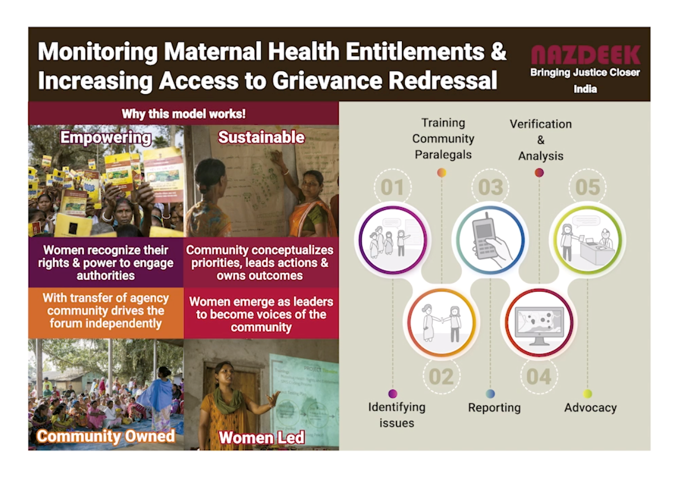

This project has allowed for grievances to get resolved locally before involving the courts. The grievance forum model is innovative due to its community-centric approach. It draws from community resources and leadership, instilling governance and active citizenry among the communities. Developing local leadership with simplification of laws has led to agency and empowerment among Adivasi women to demand rights. The use of community ownership and action makes the model sustainable. The success of the grievance forums has not only been what it has achieved by itself at the local level, but also how we have been able to use the model to amplify the voices of oppressed workers from tea plantations to different national and international platforms. It allowed us to introduce different elements in the justice process, such as administrative advocacy and community documented data. Even as a small organization working with limited resources, we were able to achieve a huge impact because the strength of the process has been that it is true to the idea of being community-centered and community-led. We focused on a slow but deliberate process of agency-building, which led to action, which then led to accountability, which finally led to the uncovering of truths that were being purposefully ignored and erased. The four pillars that made this project very effective are that it is: empowering; women-led; community-owned; and sustainable.

How can the approach of this project be applied in other parts of the world?

The project entirely relies upon strengthening existing governance mechanisms and building the capacity of citizens to access and use them. The grievance forum model places value in the hands of the community to seek accountability, and utilizes the existing legal and administrative system, helping at-risk communities assert their voices to demand implementation of their rights from duty-bearers. In our effort of replication of the same model with Dalit communities in slums in Delhi, we have seen similar impact, where communities have been able to seek accountability and build relationships with the government administrations in demanding accountability. The replicability has shown results in both urban and rural geographies, with populations asserting diverse identity struggles of women, as seen in case of Adivasi (indigenous) population in Assam and Dalit (marginalized caste) women in Delhi. The potential for replication can be viewed in the collaborations we have been able to develop in Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. The strength of the approach lies in its community ownership, and is therefore a highly replicable model.

What is next for this project?

There is a two-fold next step for this project. Firstly, we would like to replicate this model in other tea plantations across Assam, with the support of our local partners. We have already started replicating and expanding this model in districts outside of the pilot district. Secondly, we would like to amplify our work by developing solidarity across the South Asian subcontinent on improving the working conditions of tea plantation workers, especially on the issues of maternal and child health. We intend to do this by holding a regional roundtable for tea plantation workers and activists, where they can learn from the experiences of each other and work toward a regional movement for better living and working conditions. We intend to reach tea plantation communities by harnessing cross-border learning.

How has the World Justice Forum and winning the World Justice Challenge helped your work?

The award gives the much-needed recognition and visibility to the work of community paralegals in bringing access to justice closer to their communities. With the support provided by the forum, paralegals will be able to replicate this project to other communities and scale their interventions through trainings, community meetings, and administrative advocacy. The recognition at a forum like the World Justice Challenge has also helped us share information about our work with activists from across the world, who are engaged in deep-rooted community issues, and therefore creating greater awareness among international civil society about the need for an international solidarity network for improving the working conditions of tea plantation workers.

Learn more about the World Justice Challenge and all 30 finalists here, and watch the 2019 World Justice Challenge awards and more videos from the World Justice Forum: Realizing Justice for All here.