Mexico undertook historic criminal justice reform in 2008. But one critical player was left behind: the police. Now, amidst the country’s continued impunity crisis, the World Justice Project is working with local authorities to make up for lost time.

Recent killings of tourists and journalists have increased the international spotlight on Mexico’s long-running crisis of impunity. Last year, the United Nations found that only 35 of 100,000 disappearances in recent decades have been solved.

But the full extent of the crisis often fails to make headlines. In their daily lives, Mexicans face enormous barriers to justice when they are victims of a crime, whether big or small. Much of the problem relates to the way crime is—or isn’t–investigated in Mexico, a problem the World Justice Project (WJP) is now working with local authorities to overcome.

Mexican police often do not investigate crime

The 2022 WJP Rule of Law Index finds that Mexico is one of the world’s poorest performers when it comes to effectively investigating crime, ranking it 135 out of 140 countries studied. Although Mexico’s 2008 criminal justice reform created widely heralded changes to trials and the judiciary, issues with the police remained unaddressed.

In Mexico, the local police are generally not equipped or empowered to investigate crime. Their role is limited to that of first responder, and guarding the crime scene if necessary. Meanwhile, local prosecutors are responsible for investigations.

However, prosecutor investigative teams are often small in number and limited in reach. And even when police do endeavor to investigate the crimes that people report to them, they often lack training and have few formal links to prosecutors, who lead the overall process.

But there are exceptions to the rule, such as in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, and the capital city of Chihuahua, where local police have stood up promising investigative units.

What does it take to successfully transform the police?

WJP has analyzed these practices—including in the short film, Detectives of Chihuahua, while recognizing that these cities are also an exception to another general rule. These local authorities have far greater financial resources than communities across many poorer regions in Mexico.

So, starting in 2020, WJP set out to test whether transformation of the local police and their capacity to investigate crime is possible, even when resources are less abundant. With the support of the Open Society Foundations and the collaboration of local police, prosecutors and judges in Oaxaca de Juárez, WJP has found that the answer is yes.

Under the direction of Senior Researcher Lilian Chapa Koloffon, the World Justice Project helped forge a shared vision among local and state justice authorities by hosting conversations aimed at breaking down silos. For the first time, police officers, prosecutors, judges, and magistrates spoke with each other and shared the challenges they face in carrying out their duties.

New training and a first-of-its-kind manual

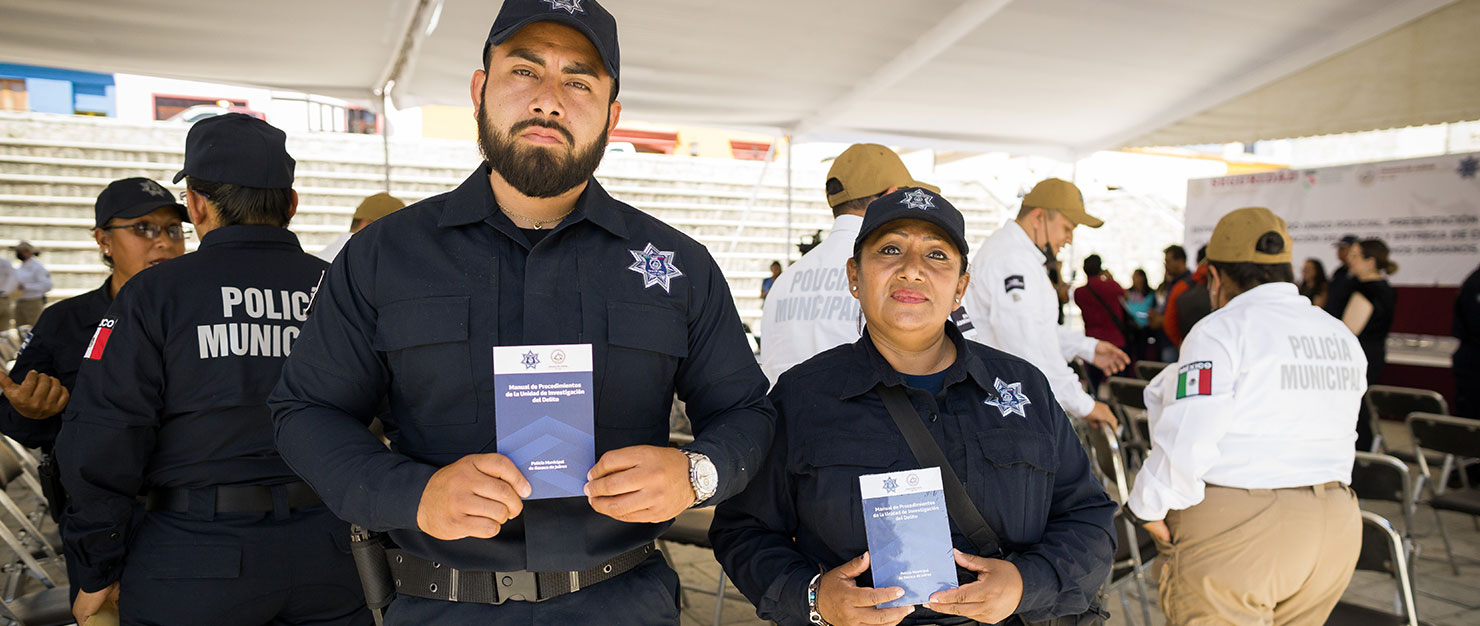

Next, WJP facilitated workshops where police and prosecutors agreed on a coordinated and constitutional process leading from investigation to prosecution. The project delivered 260 classroom hours in criminal investigation that included a gender perspective and, just this March, celebrated the creation of a new investigative manual for the local police.

“For the first time in the country, we have step by step what a police officer must do, hand in hand with the prosecutor's office, to be able to carry out investigations that can be added to the case file and used at trial,” said José Gil, the project’s training director.

The work that WJP has led in empowering the police in Oaxaca to investigate crime is designed to be replicable in other cities and regions, and that is the hope going forward.

A call for political will

However, to be successful, communities must marshal considerable political commitment, according to Chapa Koloffon. Local leaders and prosecutors, in particular, must recognize their responsibility toward crime victims, she said.

“Without this institutional work, people will continue to lack access to justice,” she said, “and impunity will continue unabated, as it has in recent years in our country.”

Learn more about the World Justice Project's work in Mexico.