Judicial reform, a critical pillar of Afghanistan’s reconstruction, has made little progress owing to the dysfunctional legal education system among other factors. Legal education institutions are not only a relatively recent development resulting from nation-building efforts of the twentieth century, but were also limited in number until recently. Despite an all-out war following the collapse of the Afghan state in the '90s, which affected the education sector, the increase in the number of legal education institutions after 2001 has been unprecedented.

Despite this progress, serious concerns regarding the quality of legal education remain. In addition to parallel legal education systems and outdated curricula, lack of educational materials, research centers, legal clinics, and a dearth of qualified professors have held back efforts of legal education reform in Afghanistan, which, if addressed, could significantly improve the justice sector.

Historically, justice in Afghanistan was administered by religious courts and informal justice mechanisms. Judges were required to have extensive knowledge of Islamic jurisprudence and local customs and were therefore trained in madrasas or religious schools. [1]

Secular education has a fairly short history in Afghanistan. The first institution of legal education was established in 1938 [2] –fifteen years after the adoption of Afghanistan’s first constitution in 1923, which necessitated the formalization of justice into law. Until 1990, there were only six public law schools in Afghanistan. [3] Private institutions of higher education – most of which offer legal education – have only been permitted in the country since 2006. [4]

Despite societal unrest in the late 1980s, a handful of higher education institutions – some of which were affiliated with various Jihadi parties – were established inside the country, and in Peshawar, Pakistan, where millions of Afghans had taken refuge. In correlation with the rise of the Taliban, the number of universities dropped from 14 to 7 in 1996. This was due to a shortage of professors, financial constraints, and the general deterioration of national security and Afghanistan’s economy. [5] During this period, women were completely prohibited from attending schools and universities.

With the establishment of the new democratic government and surge of foreign aid in 2001, the number of legal education institutions has increased impressively. Existing public law schools were revived and many more law schools in both the private and public sector have been established. The overall growth in the number of students in primary and secondary schools has increased demand for institutions of higher education. According to the Ministry of Higher Education of Afghanistan, as of July 2016, 25 public universities and institutions of higher education exist in Afghanistan, 17 of which have either law or Sharia schools, or both.[6] In addition, 122 private institutions of higher education currently operate within Afghanistan, with over 70,000 students enrolled. Ninety-six of these institutions have either law or Sharia schools, or both. [7]

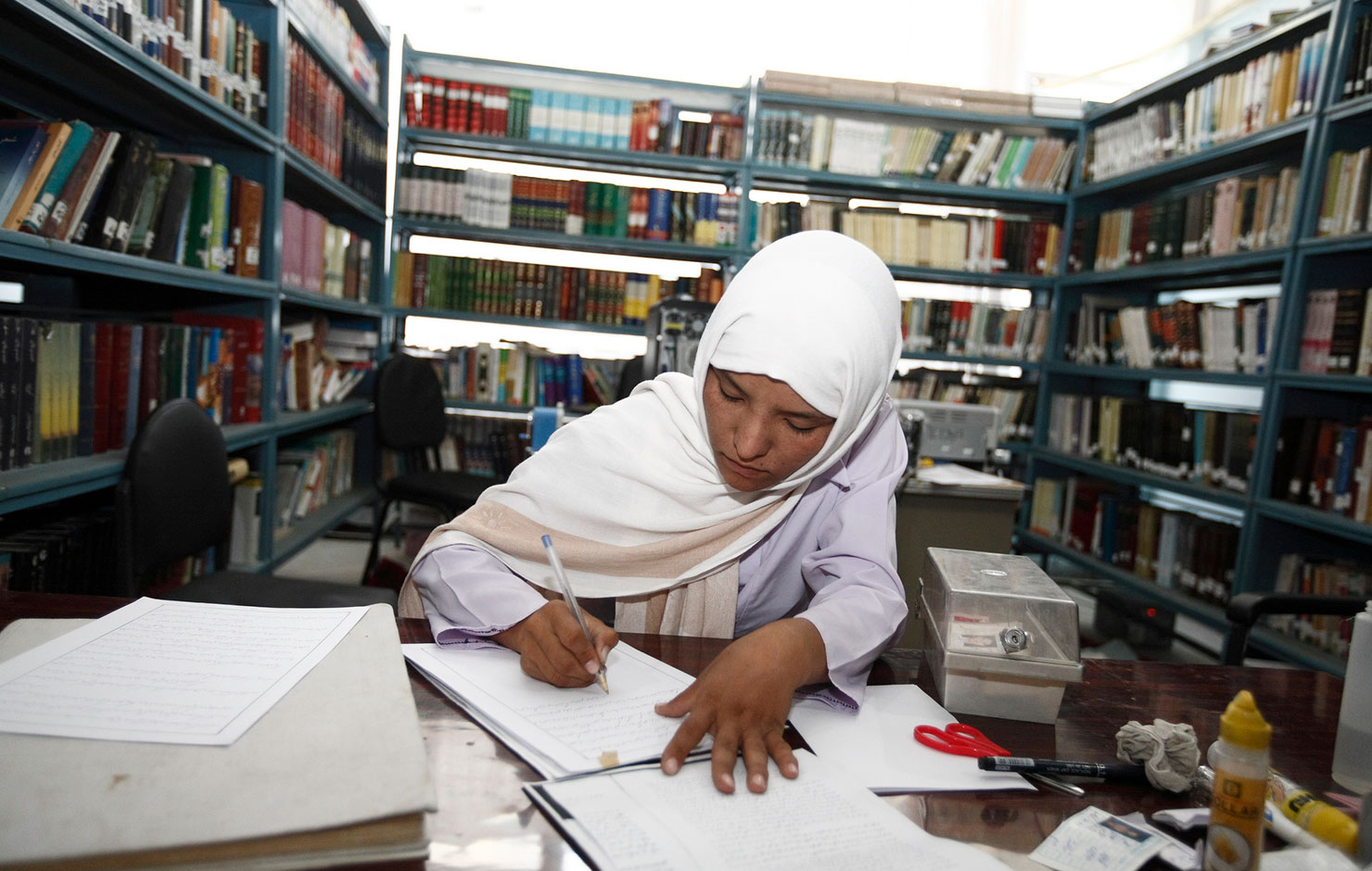

The number of women enrolled in legal education institutions has also increased rapidly since 2001. According to a 2015 report titled Legal Education Reform in Afghanistan, out of 13,462 students currently enrolled in public law and Sharia schools, 2,252 are women. Employment opportunities in the justice sector have created incentives for women to pursue careers in legal field. Based on the IDLO report: Women’s Professional Participation in Afghanistan’s Justice Sector: Challenges and Opportunities, there were 2,200 females employed in law enforcement in 2013. The same year, 120 out of 1,845 prosecutors, 335 out of 1,738 defense attorneys, and 245 [8] out of 2,296 judges across the country were women. Although the number of women in these institutions appear low in the present day and age, the growth of female employment in the justice sector since 2001 in Afghanistan is impressive.

Nonetheless, little attention has been given to the quality of legal education.

Educational reading material, such as textbooks, reference books, and scholarly literature remains limited. In 2008, the relevant stakeholders of public legal education institutions agreed to standardize their curriculum and collectively produce legal textbooks to be taught in other public law schools. [9] This effort has been criticized for hindering innovation, and producing low-quality educational material. [10] However, many private law schools have designed their own curriculum, and some have also printed textbooks. The textbooks produced by Stanford Law School’s Afghanistan Legal Education Project (ALEP), which are taught at the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF), are lauded for their quality. However, little to no scholarly literature has been produced on specific legal issues for research purposes. As a result of a shared common language, Afghanistan has benefitted from imported educational material from the neighboring country, Iran. This has been helpful to some extent, but the education gap is wider in those provinces where Pashto is the first language of communication. Despite all, there remains a huge gap of literature in Afghanistan’s legal system.

Practical skills trainings are lacking and legal clinics are not common in law and Sharia schools. Much attention is focused towards legal history and philosophy, while application of law and practical legal skills are totally neglected. [11] The teaching methodology is based on lectures and memorization. [12] Court visits and moot courts are not common, and neither research opportunities nor skills trainings are provided for the students. The few legal clinics that exist are mostly operated by NGOs, rather than being part of law schools, thus marginalizing the efforts of these clinics in educating future lawyers. [13]

The legal education and judicial institutions have neglected the demands of the profession. The curriculum has not been changed for decades. Many courses and topics such as anti-corruption law, mining law, environmental law, investigation and interrogation, anti-terrorism law, intellectual property law, international business law, money laundering, corporations, cyber security, banking law, and more are not part of law school curriculum.

Another problem facing law and Sharia schools in Afghanistan is the shortage of qualified professors with graduate level degrees, as well as a lack of research centers. The lack of graduate and post-graduate programs inside Afghanistan has made it difficult for many to pursue graduate programs abroad. Of the 380 professors in public universities, 22 hold PhDs, 71 hold master degrees, and 287 hold bachelor degrees. [14] Contrary to common law tradition, in which judges play a prominent role in the development and reformation of law, professors are instrumental to legal reform and development in civil law tradition. This is not the case with Afghanistan even though it is a civil law country. Rarely do professors take part in the ongoing discourse on legal reform in Afghanistan. There is a huge absence of scholarly literature and commentary on legal matters in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan has a parallel system of legal education. This means that there are two different schools that train students to enter the legal profession: the law schools, which have a secular approach; and the Sharia schools, which have a religious approach to legal education. Afghanistan follows civil law tradition, but is heavily based on Islamic jurisprudence. In Sharia schools, students receive an Islamic education and learn Islamic jurisprudence. Students from both law and Sharia education institutions are granted the ability to pursue a profession in law, which raises inherent concerns regarding the different applications of law in practice.

Even though law and Sharia schools share some classes, students of Sharia schools are less exposed to secular legal education. The issue becomes even more complex as some of the students at Sharia school have graduated from religious schools. They often hold opposing views on topics such as fundamental rights – especially women’s rights – and ideal types of governments, etc. On the flip side, Sharia students are well-versed on criminal law or civil law compared to students of law schools. Law schools, on the other hand, have a secular approach to law. Much attention is focused towards studying legal history and philosophy. Students gain comparative knowledge of law and take a few courses on international law. Law students, however, are not as well-versed in Islamic law as Sharia students.

Education in Sharia school is segregated, and most Sharia schools lack female professors. [15]Women are taught different curricula in Sharia schools, therefore, female graduates of Sharia school lack the skills required to enter legal profession. [16] On the other hand, law schools are co-educational and have female professors in their organizational structure. Merging the two schools can greatly benefit students of both schools, although efforts to merge them have failed so far. [17] [18]

Although great strides have been made for the improvement of legal education in Afghanistan, much remains to be done. Some of the important reforms yet to take place include the establishment of legal clinics and research centers, the provision of practical skills trainings and legal resources, changes in curriculum to respond to the needs of justice institutions and the market, graduate and post-graduate educational opportunities for professors, and the merging of law and Sharia schools are. One thing is certain: that reform in justice sector in Afghanistan depends in large part on reform in the legal educational system.