The Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (Escazú Agreement) entered into force today on International Mother Earth Day. Originally adopted in 2018 in Escazú, Costa Rica, this groundbreaking agreement is the first regional environmental treaty in Latin America and the Caribbean, and includes the world’s first binding provision to explicitly link human rights and environmental protections. It guarantees rights to access to information, public participation, and justice in environmental matters.

Since the Escazú Agreement’s adoption three years ago, 11 countries have ratified the agreement and many more have signed. The agreement is groundbreaking for the region and the world, but the hard work performed by governments and civil society to draft and adopt it will only bear fruit through implementation. Data on the extent to which environmental law is put into practice will be key for helping policymakers, researchers, and advocates monitor progress and address implementation gaps. Until recently, policymakers and practitioners in Latin America and the Caribbean have lacked quality cross-country data that can speak to these issues.

Just released in the fall of 2020, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the World Justice Project’s (WJP) Environmental Governance Indicators for Latin America and the Caribbean (EGI) represent the first-ever effort to remedy this knowledge gap by presenting new data on environmental governance in practice in ten countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Jamaica, Peru, and Uruguay. Of these countries, all but El Salvador have ratified and/or signed the Escazú Agreement.

The study generated more than 70 new indicators, coming from primary data collected through the Environmental Qualified Respondents' Questionnaire (EQRQ) administered to more than 500 in-country lawyers, academics, non-governmental organizations, and management consultants with expertise in environmental issues. Survey data from more than 230 question-level variables from the EQRQ was codified and mapped to 20 sub-sub indicators and 42 sub-indicators, as well as 11 primary indicators for each country: 1) Regulation and Enforcement; 2) Civic Engagement; 3) Fundamental Environmental and Social Rights; 4) Access to and Quality of Justice; 5) Air Quality and Climate; 6) Water Quality and Resources; 7) Biodiversity; 8) Forestry; 9) Oceans, Seas, and Marine Resources; 10) Waste Management; and 11) Extraction and Mining.

The Environmental Governance Indicators illuminate challenges and opportunities for countries in the region, and particularly speak to the Escazú Agreement topics of access to information, public participation, and justice and protections for environmental defenders. Following are key insights from the EGI that can be considered in the context of the agreement as it comes into full force.

Key Insights from the EGI

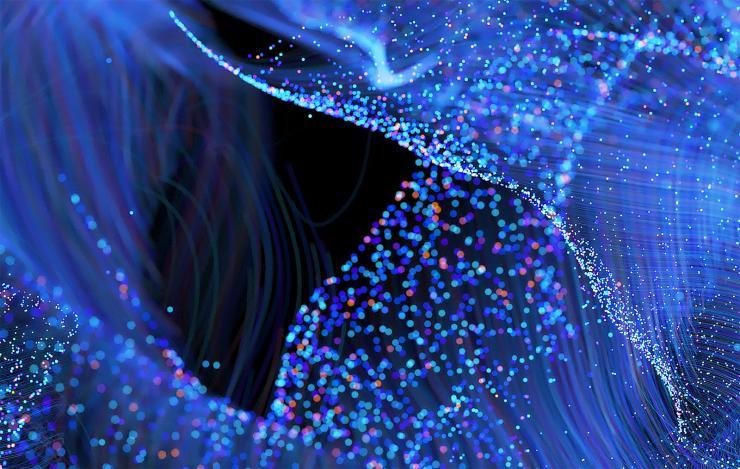

In the area of civic engagement, the region has made progress on access to information, but public participation remains a challenge.

The EGI's scores for Indicator 2 on Civic Engagement are comprised of two sub-indicators on access to information (2.1) and public participation (2.2). For most countries, the EGI shows that most countries perform better on indicators pertaining to the accessibility of environmental information than on indicators pertaining to public participation in environmental decision-making. This gap is most striking when we look at the disparity between the sub-sub indicator 2.1.1 on the accessibility of environmental information requests and sub-sub indicator 2.2.2 on due account of comments (i.e., taking into account and responding to public comments and concerns raised during the consultation process), as shown in Figure 1. A closer look at practitioners' views on who is being consulted as part of environmental decision-making reveals that some groups remain excluded from consultations. In general, state and provincial governments, local governments, and large corporations are consulted much more often than local businesses, women's interest groups, labor unions, and indigenous or customary groups (see chart: "Practitioner Views on Consultations").

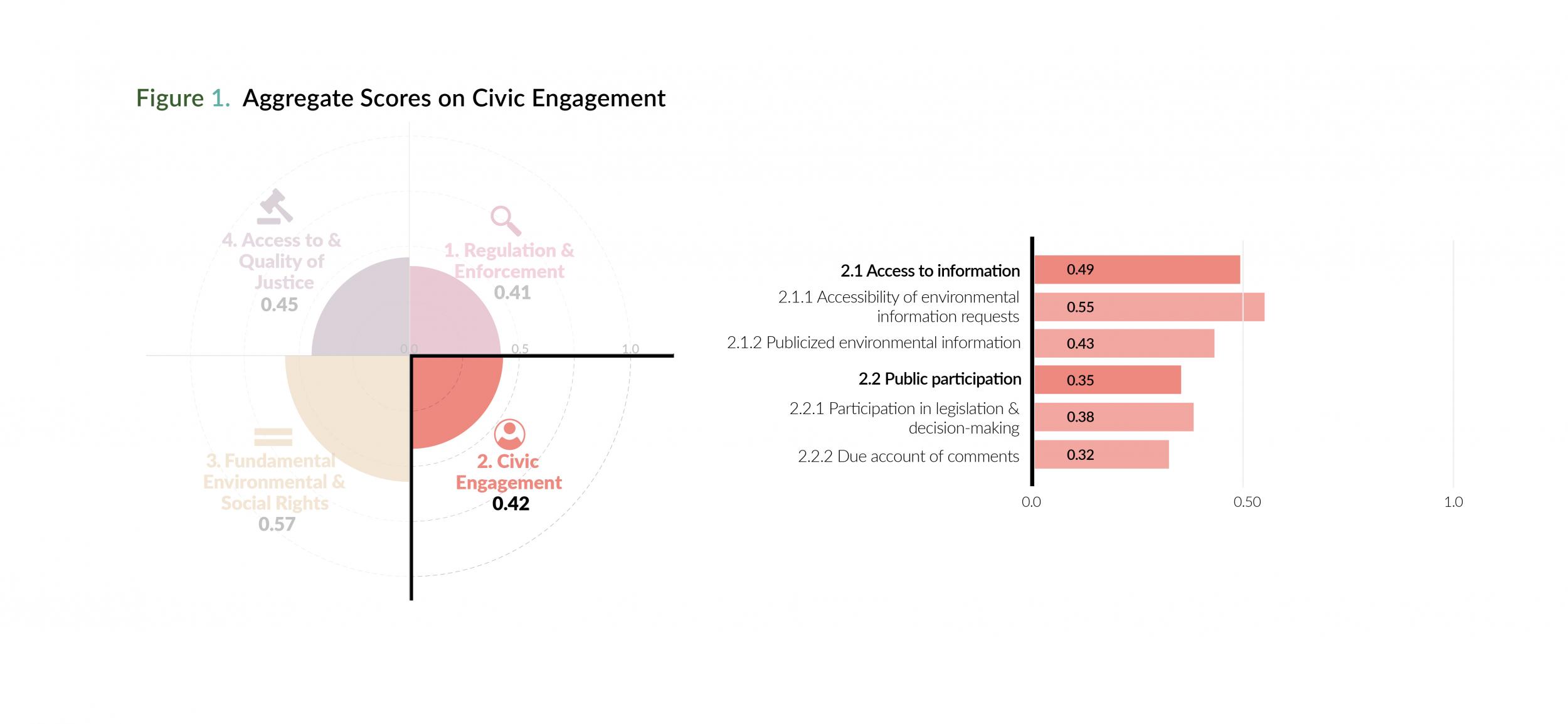

Poor accessibility of dispute resolution, due in part to complex procedures, is a justice barrier in the region.

Most countries see moderate scores for Indicator 4 on Access to and Quality of Justice. However, sub-sub indicator 4.1.1 on the accessibility of dispute resolution mechanisms stands out as a particularly weak dimension of justice (see Figure 2). The question-level data underlying this indicator shows that the most important access barriers for the general public relate to the complexity of procedures, poor public awareness, and lack of access to information (see chart: "Practitioner Views on Barriers to Accessing Dispute Resolution Mechanisms"). These are considered important barriers in all countries, even in those with a stronger overall performance in Indicator 4, such as Uruguay and Jamaica.

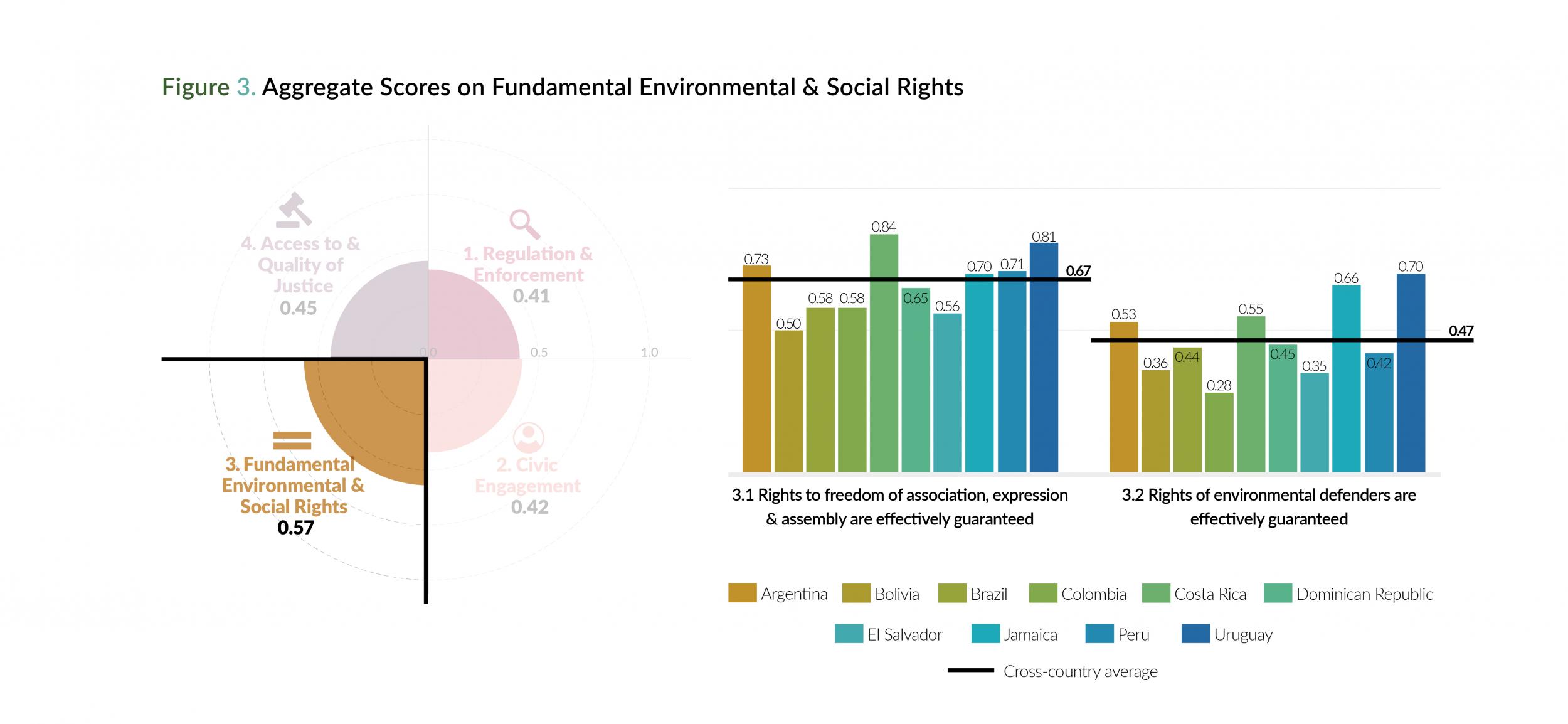

While countries perform well when it comes to the general population's rights to expression and association, the rights of environmental defenders are a concern.

At first glance, Indicator 3 on Fundamental Environmental and Social Rights appears to be the strongest dimension of environmental rule of law on average, but this aggregate score masks a disparity between countries' performance for sub-indicator 3.1—where most countries see a moderate to strong performance on freedom of opinion, expression, assembly, and association—and sub-indicator 3.2—where countries have a much weaker performance when it comes to protecting environmental defenders (see Figure 3). In many countries, practitioners think it is fairly likely for environmental defenders to be threatened, attacked, or punished. Even in countries like Jamaica and Uruguay where practitioners believe that violence against environmental defenders is unlikely, practitioners are more skeptical about the likelihood that violence against environmental defenders will be investigated and that the perpetrators would be prosecuted and punished (see chart: "Practitioner Views on Violence Against Environmental Defenders").

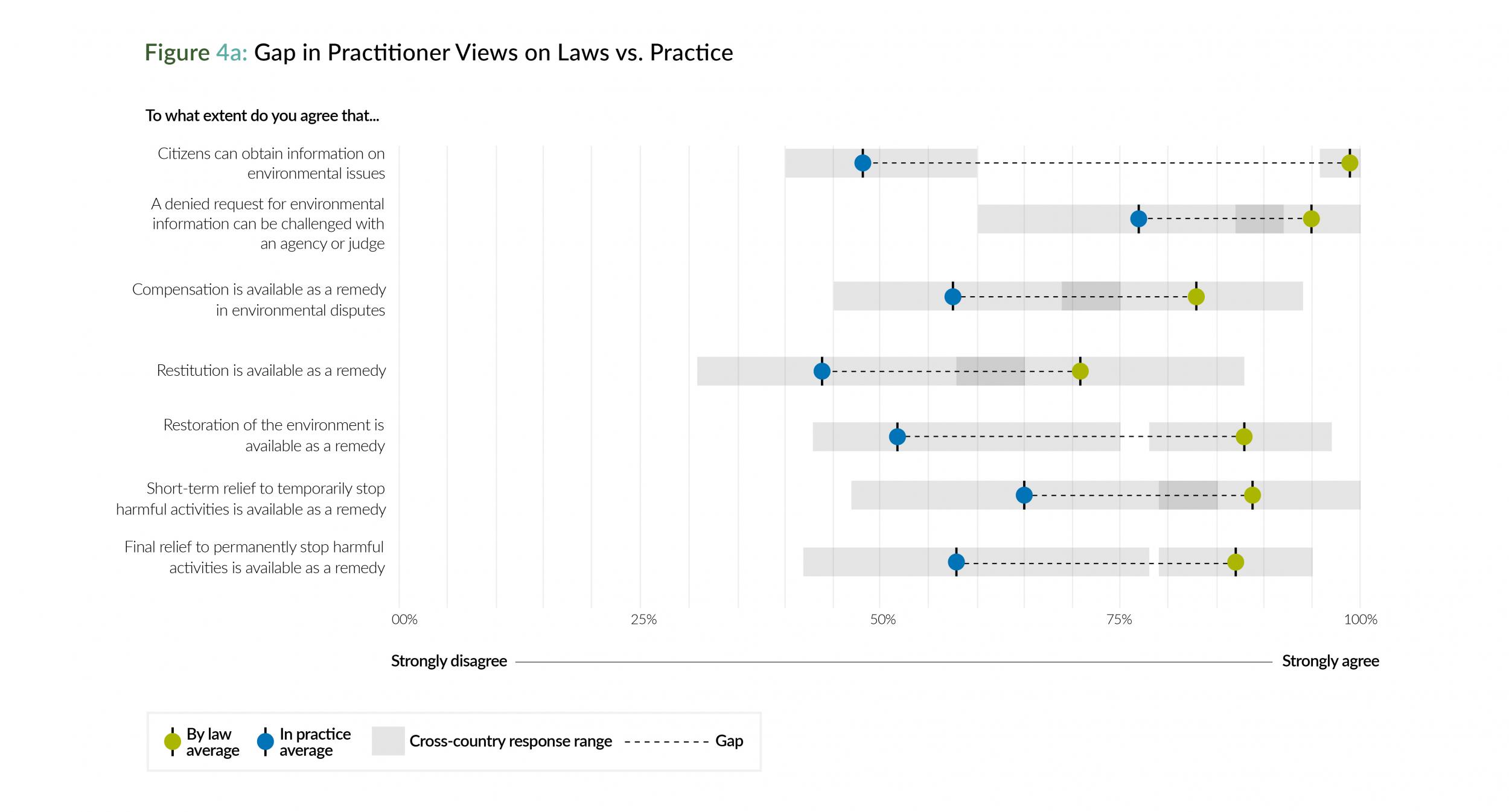

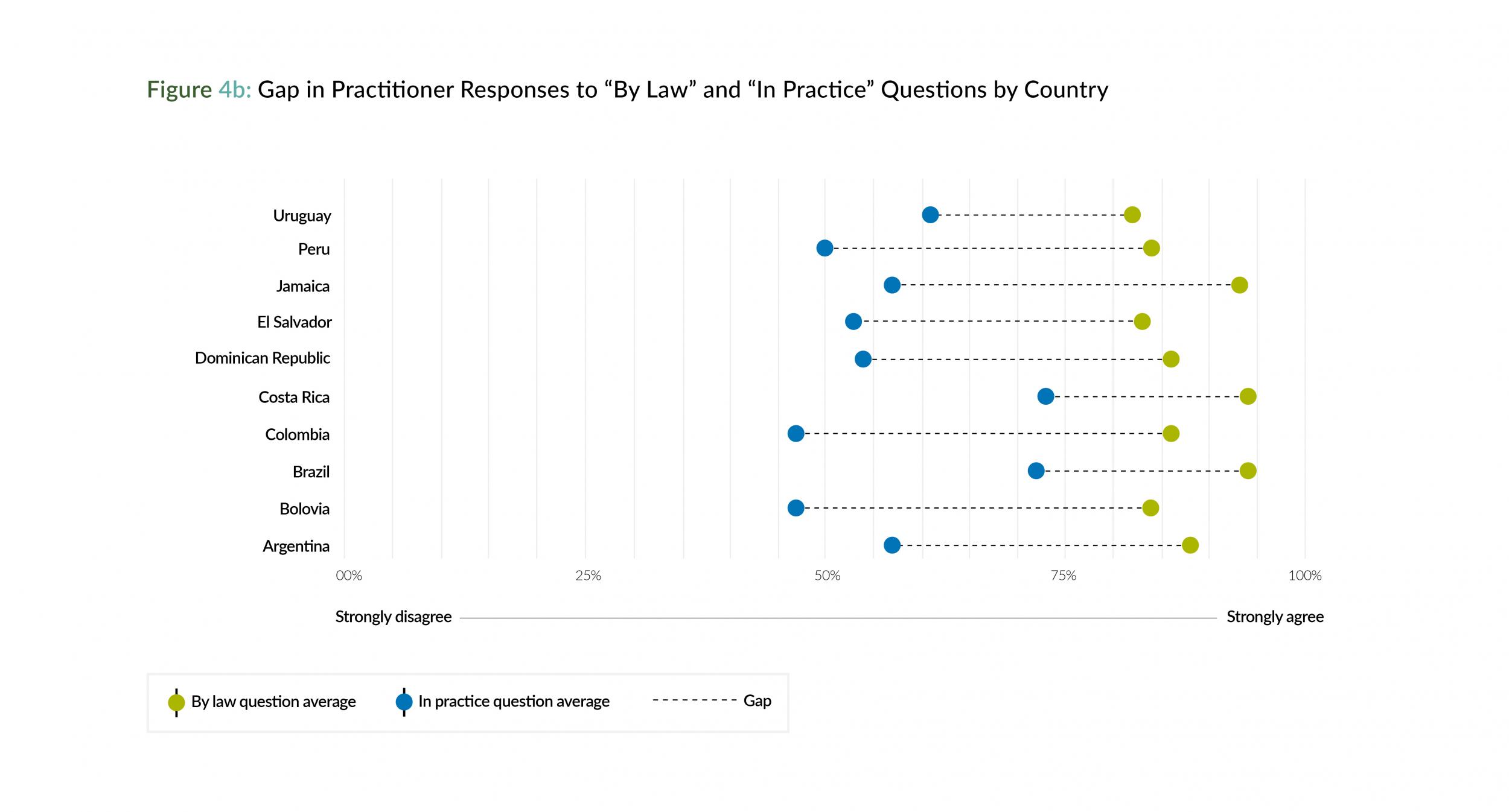

There are gaps between environmental laws and implementation in practice.

Every country included in this study has a framework for environmental laws that addresses cross-sectoral environmental issues and environmental decision-making more broadly. Nonetheless, there are gaps between the laws in place and implementation in practice. This can be seen in countries' widely varying environmental performance and in the views of practitioners surveyed for this study. When asked a series of parallel questions about the laws and practices relating to access to environmental information and judicial remedies, across the board, practitioners' views were more positive about the existence and substance of the law as compared to its implementation in practice. This trend was consistent for lawyers, academics, consultants, and NGOs surveyed for the study. Despite a wide range of responses across countries, this trend was the same within each country. See Figures 4a and 4b for a summary of perceived gaps between environmental laws on the books versus implementation in practice.

The first edition of the Environmental Governance Indicators provides valuable insights about the current state of environmental governance in Latin America and the Caribbean, and in particular speaks to key Escazú Agreement issues of improving access to information, civic participation, and access to justice in environmental matters. While the EGI shows a number of successes for particular countries and indicators, it also highlights that even countries with a generally strong performance face implementation challenges when it comes to strengthening environmental governance. It is our hope that the EGI can serve as a tool for monitoring progress under the Escazú Agreement as well as mobilize greater national action to strengthen implementation across the region.