This month, the Mexican Supreme Court announced it would hear the case at the heart of the gripping Netflix docuseries Reasonable Doubt: A Tale of Two Kidnappings. Released this fall, the series follows the nightmarish ordeal of four men who face an ever-morphing series of criminal charges despite a startling lack of evidence and recanted eyewitness testimony. Three of the men remain imprisoned in Tabasco, sentenced to 50 years for attempted kidnapping.

The film was five years in the making and part of celebrated filmmaker and WJP researcher Roberto Hernandez’s quest to investigate the impact of criminal justice reforms that his last film helped inspire in Mexico.

Unfortunately, because Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, this work has led Hernandez to leave his country in the wake of various indicators of potential retribution. In the film itself, we learn that the lawyer Hernandez hired to represent the films’ protagonists has reluctantly left the state after his van explodes before his 4-year-old daughter’s eyes.

But Hernandez remains committed to pushing for change in Mexico. Grounding his work in data and research, he believes in the power of storytelling and film to build political will for reform. “These are the tools to create social movements,” he says. “Stories have the power to dignify, and to increase the quality of our moral judgment, and to make us care.”

We recently spoke with Hernandez about the film’s backstory, and followed up to get his reaction to the Supreme Court’s announcement.

WJP: What could the Supreme Court agreeing to hear the case mean for the men you followed in Reasonable Doubt, and what could it mean for Mexico?

Hernandez: Mexico’s Supreme Court is only allowed to hear cases that are highly relevant. So the fact that the Supreme Court chose to hear the case indicates that it found significant problems that it deemed should be addressed by the highest court of the land. For Hector, Gonzalo, and Juan Luis, the protagonists of the documentary, this represents an opportunity to regain their freedom. But a decision from the Supreme Court could have implications that extend well beyond this particular case.

The Supreme Court could rule that the extremely problematic trial conditions these men and so many others face are unconstitutional. It could do something to stop the widespread use of torture as an investigative tool - or really as the go-to substitute for professional criminal investigations. The Court could also address the systematic falsification of evidence that was used against the men in the film, as well as a flawed appellate process that heavily favors the prosecution.

At the end of the day, this case offers the Supreme Court a way to restart a desperately needed criminal justice reform process in Mexico.

WJP: You joined the World Justice Project to build on the impact of your first film, Presumed Guilty. Tell us about that film.

Hernandez: It was a story of a young man who was falsely accused of a murder. And, we made a documentary about him and we showed how we got him released. It was the first time that Mexicans saw a story like this on cinema screens or on their televisions – it's the first time that they saw criminal justice at work. The film was banned about three weeks into its theatrical run by a court in Mexico, and that led it to become a pirate DVD sensation. It was sold in market stands, in the subway, and the sellers would say, this is a film your government doesn't want you to see. It remains today the most seen documentary in Mexico's history and it led to some policy change.

WJP: What did the 2008 Mexican criminal justice reform do?

Hernandez: One of the changes that was adopted very widely was videotaping criminal trials. This was a response to a problem that, in Mexico, judges would not show up in the courtroom for trials. That may seem surprising. But up until about a decade ago, the efforts of the courts were centered on producing a stack of papers that created a fantasy of a trial and the simulation of justice. So, one of the policies that we proposed after the film was launched was that the trials should be video-recorded, that there should be an objective record of every criminal trial in Mexico. And that policy gained popularity and traction, and it became adopted in legislation in Mexico. So part of the effort of this new film emerged from an idea that we could go and ask the inmates if anything had changed.

WJP: How did you get started on what would become Reasonable Doubt?

Hernandez: I came into the World Justice Project with the idea of adding the report of incarcerated persons to the data sources that WJP uses for its Rule of Law Index. And before I joined, I had managed to convince the MacArthur Foundation to give a small organization that I created, called Lawyers with Cameras, a grant to do a national survey of inmates. At the same time I had some funds from the Mexico film Institute to make a new documentary. The aim of the study MacArthur funded was to compare the experience of persons who had been tried under the old justice system with the experiences of those who were tried under the new adversary justice system.

I was about to head out to Nuevo Leon, and there was a prison riot, and there were fires in the prison. It was obviously impossible to deploy a survey there. Then a friend suggested I go to Tabasco. Macuspana, where I went, was one of the first municipalities in Mexico to implement the new system. They did a really poor implementation, but they were among the first. So there I was in the middle of the grass – it's a rural area, with a lot of cows and very hot – and it has this tiny prison. About half of the persons in my sample had been tried under the old and half under the new justice system. So it was a perfect site to do the survey.

WJP: How did you conduct the prison survey and what did you find?

Hernandez: I got there and [prison officials] gave me access and they gave me a list of all the inmates in a spreadsheet that was poorly crafted. It was the weekend and I sent it over to [WJP Chief Research Officer Alejandro Ponce], and I was like, Alex, please help me. He had to work over the weekend because it was a chaotic document [that they provided]. And he finally sent me the random draw that Monday morning, and we went straight into the prison and started interviewing.

It was just a crazy, crazy thing. We pulled off doing 450 interviews in that sample. And we learnt that most of them had been tortured during their arrest, and while in custody. Later, an independent government study conducted by INEGI interviewed a random sample of 60,000 incarcerated persons all over Mexico. And the results confirmed what we learnt in our small Tabasco survey: that Mexico continues to use torture and people are being sent to prisons, even though they're innocent. The video-recorded, oral, adversary trials are there, you have nicer litigation practices, but it's not affecting the core of the problem.

WJP: How did you meet the men who became the focus of Reasonable Doubt?

Hernandez: During that deployment [to the Macuspana prison], I met one of the men who's now the protagonist of the Netflix documentary and his name is Gonzalo. He was assigned to me to interview [for the survey]. I had an audio recorder and I was like, oh, okay, tell it to me again? Because he had initially been accused of the car crash, as you see in the film, and then he's let go for this; he’s not involved. But then, [immediately after] an arrest warrant is executed for an older woman’s kidnapping. And I'm realizing that my survey did not work for what Mexico is doing to avoid judicial supervision of arrests. And that's something I realized by doing this film. They're tricking the system in so many ways that it's just very difficult to do a survey.

It took me three hours or so to interview him. I'm tired. I'm not sure I believe him because by the end of it, I'm like, okay, you're accused of two kidnappings. I don't really trust you, but I believe your story. So I tore off a page of the survey format and I gave him my number. And so he gave the phone number to his sister and she called and called and I just never picked up. Eventually, she got on a bus and went to Mexico City to the neighborhood where I lived. And she basically said, I'm in Mexico city, I need to talk to you. And so I agreed to meet her and she got me to pay attention.

WJP: There are so many twists and turns to Gonzalo’s and the other three men’s stories and it really seems several times that things are going to work out for them. But it’s not a happy ending. What are the takeaways?

Hernandez: It's a scary lesson to watch unfold, but basically the Tabasco prosecution service was able to manipulate the entire system to get the result that they wanted, which is a 50-year punishment. And we all can see that the men are clearly innocent and they're abusing their power and they can manipulate the courts; they can manipulate the police; they can manipulate the whole system to get this outcome.

And so I think some balancing needs to happen. We need to strengthen the police forces, we need to strengthen the defense, and we literally need to weaken the prosecution service.

The [criminal justice reform] policy was implemented, but the system fails at delivering justice. It fails at recognizing an obvious case of innocence. It fails to recognize saying that these men were tortured.

WJP: The film makes the point that torture is the go-to substitute for professional police investigations, and that police officers don’t have the power or training to change this. How prevalent is torture?

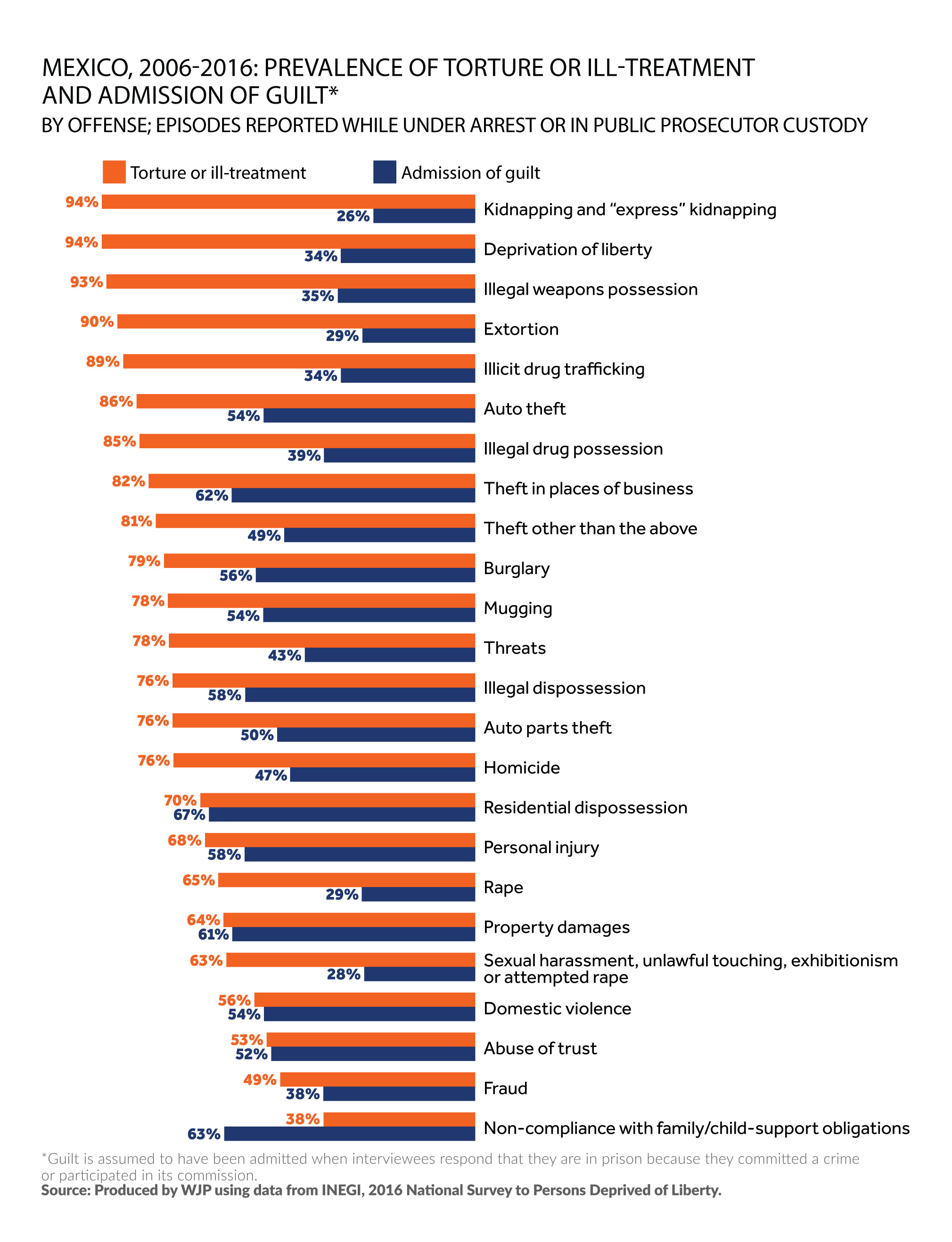

Hernandez: We have it in a WJP report titled Failed Justice. We did an analysis using the large governmental survey conducted by INEGI, breaking it down by type of crime, [based on] a random sample of 60,000 inmates. The survey respondents are asked numerous questions about a variety of forms of torture and mistreatment.

When we do the arithmetic, we conclude that 79% of inmates say they were tortured [or abused]. 94% of inmates say they were tortured when they were accused of kidnapping - 94%! But only 26% of these inmates told the INEGI surveyor, yeah, I did it. I kidnapped somebody. Okay. So that means that 74% didn’t. And of course, you can have bias, maybe 5 or 10%. But if you look at the shape of the chart [see below], what you can see is, the more torture [is being used], the less likely [the accused is] to be guilty. What you see is that, if you use violence, you're more likely to induce error in adjudication.

That's exactly the conclusion that I wanted people to see. I didn't want an argument [against torture] based on human rights language. I wanted to speak to the pragmatists. To those who are willing to torture because they think it works because some people think it works well. Some people think you can obtain reliable evidence through torture. It is not so. Torture does not work. Here's the evidence.

WJP: How did all this come to be? The WJP Rule of Law Index, Mexico ranks 129 out of 139 countries for criminal justice, and 137th in effective criminal investigations. An expert in your film says the Mexican justice system was not designed to find the truth, but to be a system of political control. What did she mean?

Hernandez: We had kind of a soft dictatorship in Mexico. It had an appearance of an electoral democracy, you know, with elections taking place periodically, but a history of 70-years of a one-party rule and the justice system being used against political dissidents. They're accused of a crime and then they're put in prison. And just four weeks ago, this happened. A high-ranking employee of the Senate was arrested and he's now in prison in Veracruz. So that's the history that we have. Authoritarian systems need to have judicial and investigative processes that can be manipulated. In Mexico’s old justice system, you could just write whatever you wanted in the court documents and make that become the official truth. Of course, when you have an oral trial with a public hearing that is video-recorded it's no longer as easy to do that. But it's still possible to do it as we show it in the film.

WJP: In the film, you tell the men that the political cost is high to let accused kidnappers free in Mexico, even if they’re innocent.

Hernandez: This idea of releasing people who are accused of kidnapping was put to the test a few years ago. A woman named Florence Cassez, a French national, was accused of kidnapping, and the story is just ridiculous. She's accused of coming from France to Mexico to kidnap the maid of some guy. So to me, that's outrageous because it doesn't sound like a very lucrative kidnapping. Yet the people bought this story, really believed it, and it had all the flags of a made-up case.

The president of France at the time, Sarkozy, comes to Mexico and he is given the chance to address Mexico's Congress. He chose to speak of the case, and then he was asked to leave Mexico. Basically years later, Mexico’s Supreme Court ordered this woman to be released. And it was a huge scandal. All the front pages of Mexico covered this story negatively, saying “the French kidnapper is going to be released, this is outrageous,” etc. Not for one second giving a thought to the possibility that she was innocent! She's now back in France, but that's the size of the costs that I'm talking about.

WJP: How do you overcome that?

Hernandez: I think the best tool is to meet people where they are. And where we are is, we think that we are likely to be victims of crime, but we don't think we're likely to be victims of a false accusation. And so that's the journey that this series proposes to us. It's like, okay, I'm going to show you how easy it is to end up in prison.

WJP: Would it be fair to say that the public is more upset about impunity in Mexico than they are about unjust convictions, but that the two are related?

Hernandez:I think it is fair to say that most Mexicans are more concerned about impunity than they are about torture or illegal arrests or violations of the process during criminal prosecutions. Our research showing that 79% of inmates were tortured or mistreated when arrested and taken into custody shows that police lack tools to conduct fair and competent investigations.

When the police resort to violence and to corrupt or illegal methods, they deplete citizen trust, and they are left with fewer informants and less information to legitimately solve cases. This certainly contributes to impunity. And so does locking up innocent people for 50 years. The people who actually commit the crimes remain free to kidnap, rob, and kill again. We are all living with the heavy consequences of a system that imprisons the wrong people.

Learn more about the World Justice Project’s Criminal Justice work in Mexico: