In early March, at the 59th Session of the Commission on the Status of Women, UN representatives, politicians, and civil society practitioners gathered to take stock of the progress made towards gender equality two decades after the landmark Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. The issue of political participation and representation typified the conclusion made over a host of concerns: there has been progress, but not quite enough. A report led by the Gates and Clinton Foundations, simultaneously released with the session, found that the rate at which women hold all political office has doubled since 1995, and increased in national legislatures by 12 percent. Such gains, however, mean that women still hold only 22 percent of national legislature seats around the world.

In early March, at the 59th Session of the Commission on the Status of Women, UN representatives, politicians, and civil society practitioners gathered to take stock of the progress made towards gender equality two decades after the landmark Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. The issue of political participation and representation typified the conclusion made over a host of concerns: there has been progress, but not quite enough. A report led by the Gates and Clinton Foundations, simultaneously released with the session, found that the rate at which women hold all political office has doubled since 1995, and increased in national legislatures by 12 percent. Such gains, however, mean that women still hold only 22 percent of national legislature seats around the world.

One common question about this unequal gender representation is whether it is a reflection of unequal active citizenship in lower-stakes areas of political participation. Our new report, the World Justice Project (WJP) Open Government Index 2015, uses representative population polling and surveys of in-country experts to shed light, for the first time, on open government practices in over 100 countries. Polling from our Index provides, among many dimensions, novel and empirical findings on the state of political participation across countries and across demographics.

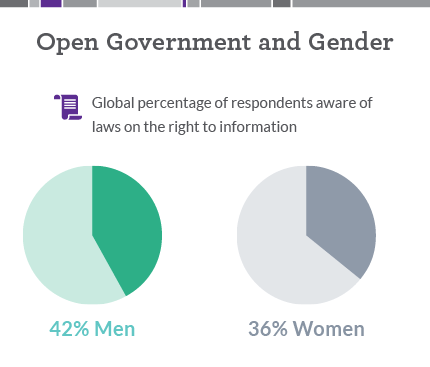

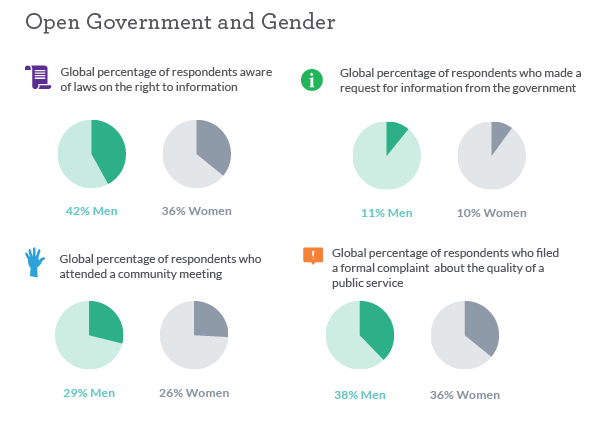

Original data from our report indicate that gender disparities on a number of methods of civic participation are much smaller than unequal political representation would suggest. In fact, disparities were often nonexistent: women are roughly as likely as men to engage with government institutions through a number of advocacy methods. Specifically, while men were slightly more likely to know about right to information laws worldwide, women were as likely as men to request information, file complaints against public services, and attend community meetings.

The largest gender disparity was found in “awareness of right to information laws,” where men were often signifcantly more likely to express familiarity with these laws. In half of all countries surveyed, women were less aware of laws supporting their right to access of government-held information. Specifically intriguing were the results for the countries with the highest scores on this question: Western European countries that scored well above the global average also had the largest gender discrepancies, often ten or twenty percentage points (See: Austria, Sweden, Netherlands, United Kingdom). One explanation for this phenomenon could include an absence of concerted efforts seen in some developing countries to broadly publicize right to information laws.

When it comes to actually requesting information—rather than knowledge of those laws—there is wide gender parity, with few countries demonstrating a significant gap. Women were as likely as men to request information in three quarters of countries surveyed. Nonetheless, only 10 percent of both men and women report requesting information from government.

More intensive types participation, like filing a complaint about the quality of public service and attending community meetings, also proved to have relatively small inequalities. In filing complaints, for example, 86 percent of countries showed no statistical difference in gender participation. While more countries have discrepancies in who attends community meetings, women also have greater participation rates in community meetings in many countries, a state of affairs particularly visible in Eastern and Southern Europe and Central America. Since Index data is drawn from urban centers, it is also possible that female participation in countries with large rural populations—some of which women are more available to attend meetings—are not adequately represented by these results.

Overall, while total requests for information, complaints, and attending community meetings are relatively infrequent for the entire global population, gender does not seem to be a defining determinant of this type of participation. Though each of these actions may be considered oriented towards personal advocacy more than public service—and ad hoc versus sustained political engagement—the relative parity should still be contrasted to the vast inequality in legislative and representative politics.

At the very least, this new data suggests a willingness of women around the world to engage and advocate against the government far more than higher level political representation reflects. Moreover, since the largest gap is in awareness, not willingness to participate, this finding should be encouraging for equality advocates. Still, attention is warranted: both where gaps are found, and to best practices in countries that show gender parity.

If nothing else, we hope our new data on ground-level participation can help civil society and governments better identify the structures and behaviors that currently obstruct egalitarian political representation as we move in to the next twenty years.