In Europe, a long-anticipated showdown over rule of law backsliding in Poland and Hungary reached a critical milestone today. The European Court of Justice rejected the two countries’ objections to a 2020 regulation that allows the European Union to cut some member state funding based on rule of law performance.

How did it come to this? And where does this leave the rule of law in Europe and the EU’s ability to stop its unraveling amid wider global trends? We talked to Princeton University Professor Kim Lane Scheppele, an expert on constitutionalism and international law, a foremost scholar of rising authoritarianism, and a member of the World Justice Project’s research consortium.

WJP: First of all, what has fueled this rule of law confrontation with the European Union? Let’s start with Hungary.

Scheppele: In 2010, Viktor Orbán became Prime Minister of Hungary when his Fidesz party won two-thirds of the seats in the Parliament in a free and fair election. Under Hungarian law, the constitution may be amended with a single two-thirds vote of the unicameral Parliament. So Orbán used his constitutional majority to heavily amend the old constitution he inherited before writing a wholly new one.

His loyal Parliament also enacted thousands of pages of new laws, changing the Hungarian constitutional order from top to bottom, all with the effect of concentrating power in Orbán’s hands and cementing one-party control over the state. The judiciary has been captured – all by law. The formerly independent institutions – public prosecutor, central bank, election commission, media board, audit office, ombudsman’s office, data protection official and more – have all been packed with party loyalists.

WJP: Why is the EU just taking action now, 12 years later? And what about the opposition?

Because Orbán took every step according to law (even if the law was passed the day before it was used), the European Commission has had trouble figuring out what to do about it even though the steady concentration of power in the prime minister’s hands has destroyed constitutionalism as a system of limits on the state.

Across the board in Hungary, the conditions for a robust democracy no longer hold. The opposition parties have been harassed and are fragmented; the media are governed by a party-controlled regulatory board and are no longer pluralistic; civil society has been defunded and demobilized. An election is coming up in April 2022, and the battered opposition parties have joined together in a concerted bid to unseat Fidesz, but the election laws have been so heavily tilted in favor of the governing party that it is unclear whether it can be defeated at the ballot box. Most international democracy-rating organizations – like Freedom House and V-Dem – no longer rank Hungary as a democracy.

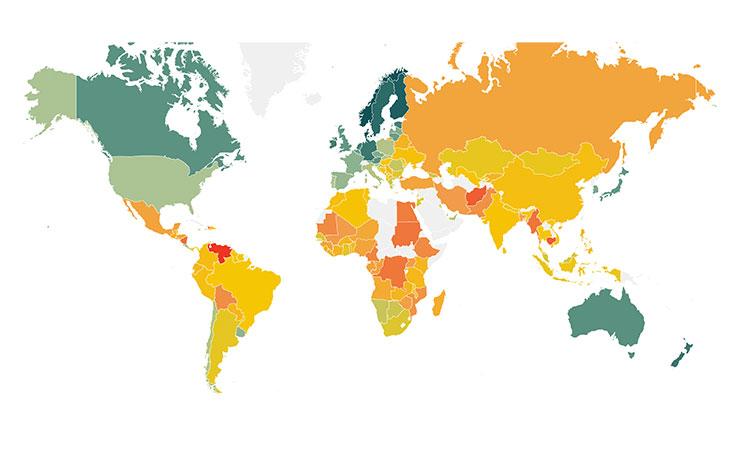

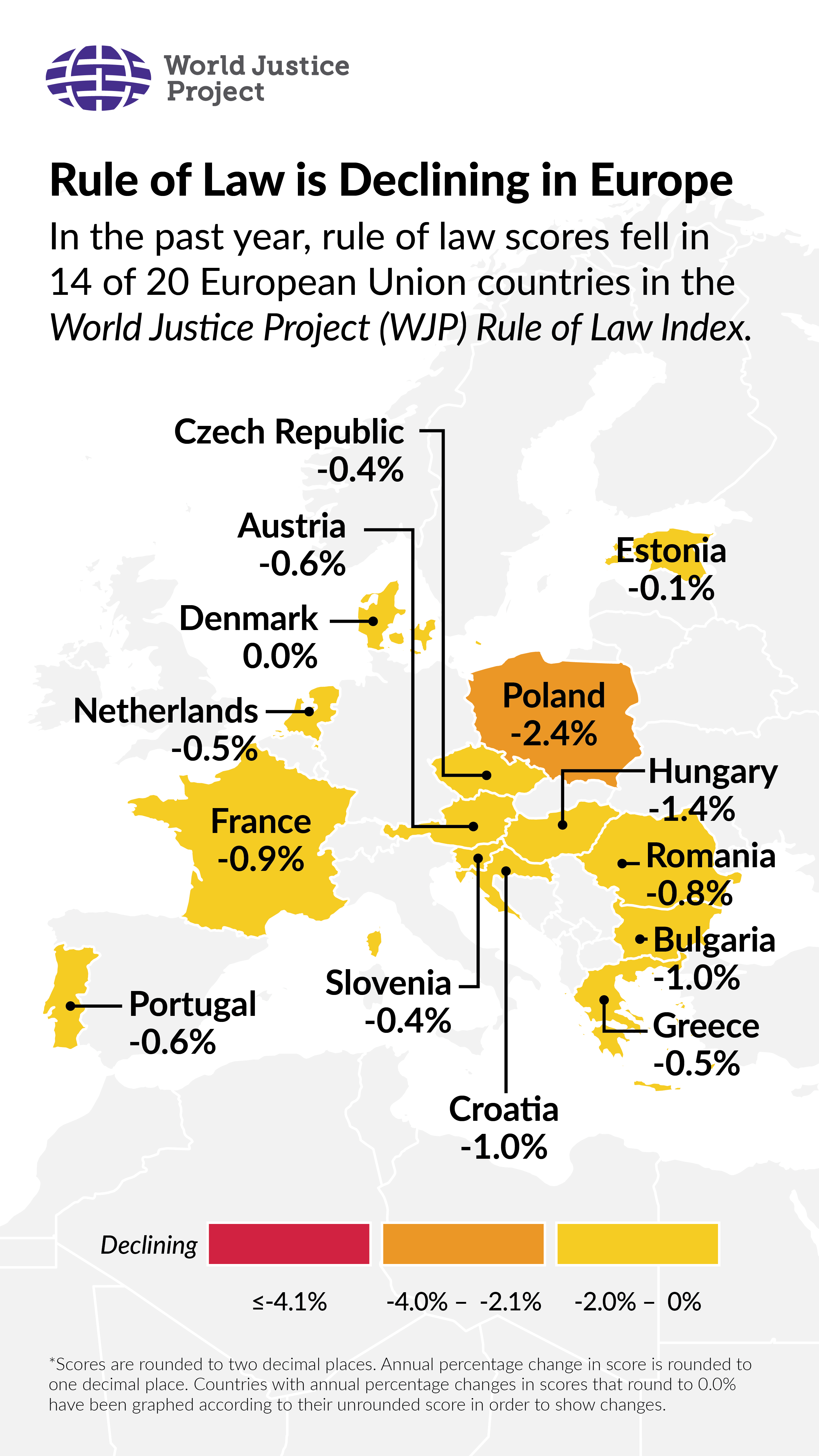

WJP: The WJP Rule of Law Index has also captured a major decline in the rule of law in Hungary. It ranks below Kazakhstan, Malawi and Indonesia, and is last in the European Union. Poland still ranks ahead of Romania, Croatia, Greece, and Bulgaria, but it has also experienced a sharp decline in rule of law – actually a sharper decline than Hungary in the last couple years. What’s happened there?

In Poland, the story is slightly different. In 2015, the Justice and Life (PiS) party won the presidency and simple majorities in both houses of Parliament in free and fair elections. But under the Polish constitution, this did not give them a constitutional majority. Once PiS had the power to govern by ordinary law, however, it started attacking the judiciary in particular, packing the constitutional court with illegally elected judges, firing court leaders up and down the system to replace them with their own hand-picked judges, creating a new disciplinary chamber to punish judges who rule against what PiS wants and flaunting EU law whenever the Polish government wants to do something else. The Polish government has also brought under its control the public media, prosecutor’s office and ombudsman’s office.

In Poland, the story is slightly different. In 2015, the Justice and Life (PiS) party won the presidency and simple majorities in both houses of Parliament in free and fair elections. But under the Polish constitution, this did not give them a constitutional majority. Once PiS had the power to govern by ordinary law, however, it started attacking the judiciary in particular, packing the constitutional court with illegally elected judges, firing court leaders up and down the system to replace them with their own hand-picked judges, creating a new disciplinary chamber to punish judges who rule against what PiS wants and flaunting EU law whenever the Polish government wants to do something else. The Polish government has also brought under its control the public media, prosecutor’s office and ombudsman’s office.

The Polish case differs from the Hungarian case because much of what the Polish government has done has not been legal even under Polish law, let alone under EU law. The key player in the Polish case, Jaroslav Kaczynski, is officially speaking just an ordinary member of Parliament so he controls from behind the scenes without being reachable through impeachment or votes of no confidence, the usual ways of controlling an executive. Because of the extra-legal nature of the Polish assault on the rule of law, the European Commission has been much more active than in the Hungarian case, bringing infringement actions and winning European Court of Justice (ECJ) judgments to force dismantling of the system of controls over judges. Also, in the Polish case, it has been primarily the judiciary that has been the target of PiS attack.

Poland still has a vibrant civil society, strong opposition parties, some media pluralism and an election framework that has not yet been corrupted. Democracy-rating organizations classify Poland as a backsliding democracy whose rankings are dropping precipitously but not yet as a hybrid regime.

WJP: OK, so what led up to Hungary and Poland filing the complaint against the EU that the court ruled on today?

Scheppele: In 2020, the EU finally passed the Conditionality Regulation, which allows the EU to cut funds to states whose rule of law violations interfere with the proper spending of those EU funds. Hungary and Poland could see from the start that they stood to lose the most under this Regulation because they have been the biggest violators of the rule of law. First, they attempted to undermine the Regulation all the way through the legislative process. They managed to narrow its scope and make it much less effective than when it was first proposed because, instead of disciplining states for violating the rule of law by withholding funds, the Regulation instead cuts only those funds whose proper spending has been directly affected by the rule of law problems. So, for instance, it could cut funding if challenges to the distribution of funds within the Member State were adjudicated by a judiciary that is no longer independent, or a if the public procurement system routinely distributed EU funds primarily to regime cronies, or if a public prosecutor’s office failed to prosecute corruption in the use of EU funds by the ruling party. The Regulation in the end is much less effective at fixing rule of law violations more generally than it is at protecting EU funds because every case where funds are withheld has to be directly traceable to the spending of EU funds. Even in this weakened state, however, the Regulation can still make a difference because in both Hungary and Poland, the violations are systemic and affect the spending of EU funds among many other things. .

The Regulation required only a qualified majority to pass at the Council of Ministers (where states vote as states as part of the ordinary legislative process). But in December 2020 when it came up at the European Council (where heads of state and government meet to discuss general policy), Hungary and Poland could see that they did not have the votes to block it. So when it looked like the Regulation was going to be enacted even over their objections, they tried to scuttle it at the last minute.

At that European Council meeting, on the eve of the Regulation’s passage, Hungary and Poland threatened to hold hostage the whole budget – which requires unanimous agreement – unless the Regulation were dropped. The European Council held firm on the Regulation, but agreed to a compromise. It gave instructions to the European Commission (unlawful instructions, by the way –because the European Council is not a body that can vote on legislation) to pause before enforcing the Regulation until its legality could be challenged at the Court of Justice. Poland and Hungary waited until the last possible day to file the case because they wanted to extend the delay as long as possible. This benefited Orbán in particular. If he couldn’t prevent the Regulation from being enacted, then at least he could try to prevent its enforcement until after the election coming up on April 3. So here we are.

WJP: What did the Court decide, and how significant is this decision for those who care about rule of law?

Scheppele: As expected, the Court of Justice upheld the Conditionality Regulation as a lawful exercise of the EU’s law-making power and therefore rejected both the Polish and the Hungarian challenges. The only question was how narrowly the Court would read the scope of the Regulation. And the answer is: narrowly in some ways and broadly in others.

On the “narrow” side: the Court emphasized that rule of law violations like failure to maintain an independent judiciary or failure to ensure the absence of conflicts of interest in the awarding of contracts could only be reached through the Regulation if they directly affect the “sound financial management” of EU funds. As the Court summarized in its press release on the case, “the regulation is intended to protect the Union budget from effects resulting, in a sufficiently direct way, from breaches of the principles of the rule of law and not to penalize those breaches as such.” So the withholding of funds under the Conditionality Regulation cannot be used as a punishment for rule of law violations, but only as a means of keeping EU funds out of unsafe hands.

On the “broad” side, however: the Court finally established that the values on which the EU is founded - including rule of law but extending to all of the values mentioned in Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union – may be enforced in many different ways and not just through Article 7. As the Court emphasized, particularly in its Polish judgment in this case (because Poland has been resisting other judgments of the Court of Justice on this point), judicial independence may be enforced directly through the Charter Article 47 right to a fair trial and the TEU Article 19(1) requirement that all member states develop effective remedies for legal breaches, for example. The Court implied that the Commission could bring forward even more regulations getting at different aspects of the rule of law by grounding them in other sections of the treaties.

Perhaps most crucially for those who care about the rule of law, however, the Court rejected the idea that the rule of law cannot be used as a standard for assessing the conduct of states because it is too vague or because states may have their own distinct approaches on the subject. As the Court said in the Hungarian opinion at paragraph 234:

Whilst they have separate national identities, inherent in their fundamental structures, political and constitutional, which the European Union respects, the Member States adhere to a concept of ‘the rule of law’ which they share, as a value common to their own constitutional traditions, and which they have undertaken to respect at all times.

It is this common conception that can now be used to assess whether violations of the rule of law sufficiently and directly affect the spending of EU funds enough that such funds can now be withheld for that reason. The definition of the rule of law in the Article 2(1) of Conditionality Regulation itself is quite sweeping:

‘the rule of law’ refers to the Union value enshrined in Article 2 TEU. It includes the principles of legality implying a transparent, accountable, democratic and pluralistic law-making process; legal certainty; prohibition of arbitrariness of the executive powers; effective judicial protection, including access to justice, by independent and impartial courts, also as regards fundamental rights; separation of powers; and non-discrimination and equality before the law. The rule of law shall be understood having regard to the other Union values and principles enshrined in Article 2 TEU;

In short, EU law now has a definition of the rule of law that can be legally enforced.

WJP: How did the Court ground its decision making?

Scheppele: The Court’s argument turned centrally on the “legal basis” for the Regulation, since all EU law-making must stay within the boundaries set by the EU Treaties by pointing to an article in those treaties that specifically authorizes the law in question.

In this case, the Commission had grounded its power to regulate on the section of the treaties that gives the Commission the responsibility to oversee the budget and the proper use of EU funds. The Commission had argued that rule of law violations could affect whether EU funds were properly managed and so were no different than the other criteria that the Commission had used in other financial regulations to assess the propriety of EU spending, all of which had been enacted using the ordinary law-making procedure.

By contrast, Hungary had argued that rule of law violations had nothing to do with the budget since achieving the rule of law could not be a goal of the budget itself. Instead, Hungary argued, Article 7 of the Treaty of European Union was the appropriate legal basis for dealing with rule of law problems and therefore EU values could only be enforced through a procedure that required the unanimous vote of all member states save the one criticized. Of course, this argument would lead to the non-enforcement of the rule of law, because Hungary and Poland could veto sanctions against each other now that there are two rogue states in the EU.

In today’s judgment, the Commission won and will, we hope, begin to enforce this Regulation immediately.

WJP: How do you expect this decision to play out practically and politically?

Scheppele: The Commission has said all along that it will take into account all violations of the Regulation going back to the date it came into force on January 1, 2021. From what we can tell from outside the system, the Commission seems to have prepared letters of notice to start the process specified in the Regulation at least against Hungary and perhaps against Poland. They’ve at times also hinted that they will notify more countries that there are rule of law problems that they must correct.

The enforcement process opens with a “dialogue” in which there is some back and forth between the offending state and the Commission to see if the offending state will take action on its own to fix the identified problems before the Commission recommends to the Council that funds be cut. And then the Council has to approve the recommendations by a qualified majority before the funds stop flowing. Though the process has various short deadlines throughout, it will nonetheless take at least four months from the time that the process starts before funds would stop – and that’s if all steps are completed in a timely way and the Council accepts what the Commission proposes. Probably it will take longer.

Orbán has so primed the Hungarian population for the cuts that he already has his narrative ready to go. According to Orbán, the EU wants to take away Hungary’s money because the EU is culturally leftist and trying to impose its views on Hungary while Hungary defends Christian conservatism. The new president of the Supreme Court in Hungary has called the EU a totalitarian regime imposing itself on Hungarian sovereignty. Orbán and others in the Hungarian government have compared the EU to the USSR. So Orbán will try to make it look like the funding cuts result from the rest of the EU trying to impose its alien values on Hungary. Expect a giant culture war to follow if the Commission starts to enforce the Regulation.

WJP: Who comes out stronger and weaker? And what about the rule of law itself?

Scheppele: In the legislative process leading up to the Conditionality Regulation, the rule of law got rather lost. Instead the Regulation emerged as a sort of corruption-fighting measure designed to keep EU funds from being misspent rather than a Regulation designed to restore the rule of law. That said, there’s so much wrong in Hungary and Poland that the rule of law issues (like judicial independence, arbitrary legislation and reduction of checks and balances) eventually make corruption more likely so it is possible to reach some crucial rule of law issues with the Regulation. But the Commission lost control of the Regulation and now it doesn’t do what it should have done. And the Commission caved into the European Council delays. It should have been a more general rule-of-law fighting tool that could have been used immediately.

Who emerges stronger and who is weaker? If Orbán loses the funds, he will be in a pickle because he’s already spent much of the money and the state budget would have to make up the shortfall. If the opposition wins the election, it gets saddled with debt unless the EU relents. So Hungary, regardless of who is in power after April 3, will eventually be a loser.

But if the EU had moved faster to start the process of cutting funds years ago, the condemnation of Orbán by EU institutions might have made a difference in the current election. Hungarians – and Poles too – are very pro-EU so it matters if the EU sanctions them. But while a funding cut-off is waiting in the wings, it will come too late to influence the election. Orbán may, as a result, get four more years in power before the reckoning comes.

The EU may appear to have done something about autocrats in their midst, but this is too little, too late. That said, it’s better to do something than nothing.

WJP: How does this conflict reflect global trends, and what lessons are most relevant elsewhere?

Scheppele: In discussing democratic backsliding, we’ve concentrated primarily on the constitutional aspects – the destruction of checks and balances, the loss of protection of rights, the harm to independent institutions like courts, human rights defenders, elections commission and more. All of those things matter. But in the end, backsliding democracies in practice wind up collapsing economically because economies can’t be run like personal piggy banks. Investors won’t invest. Foreign lenders won’t lend. This is a terrible outcome for the populations of these countries as we can see in contemporary Venezuela. But those cases tell us that we should not forget about the economics of democratic collapse. Cutting funds to rogue states may be a harsh solution, but it does hasten domestic democratic accountability. That said, it may cause so much pain that it should only be used as a last resort.

WJP: What do you think it would take to turn the authoritarian tides?

Scheppele: Twelve years into the Orbán regime and seven years into the Kaczynski regime, many people have been hurt, institutions have been damaged, judiciaries have been corrupted and it will take a long time to build back democracy again. But if international funders of these collapsing democracies withhold funding, it may hasten a domestic reckoning. And then the international funders can restore funding when a new legitimate democratic regime wins office. “Follow the money” was how journalists brought down Richard Nixon in the Watergate scandal. And “cut off the money” may be the most effective way to bring down aspiring autocrats now. But it would have been so much better to act earlier when fixing the problem would have been so much easier because these regimes were less entrenched.