Urbanization is an inexorable trend of humanity. Human beings tend to congregate in always larger clusters and today’s megacities tend to grow in conurbations.

Two of the largest cities in Brazil, Rio and Sao Paulo, are an example of this trend of urban development. You can travel between them almost without seeing a single stretch of bare land. Small and large cities pave the way from one to the other of the big cities.

Is this growth sustainable or does it bring with it seeds of social disruption is the big question that Jaana and the McKinsey Global Institute bring to our attention.

I remember that in the eighties of the last century, Arnold Toynbee edited the joint contribution of several historians and sociologists in a beautifully illustrated book called The Ideal City. They selected several cities of the world at the historic moment of their peak and tried to determine what conditions made them special for fostering civilization. They were not selected in consideration of their density or material wealth but basically for the relevance of their cultural production and the quality of life they offered to their inhabitants.

Among them were Tenochtitlan as Mexico City was called before the Spanish conquest, Athens at the time of Pericles, Rome under the rule of the Emperor Augustus, and Goethe’s Weimar.

With millions of people living close together, literally piled up in high-rises like the ones we are among right now, the adherence to the rule of law is even more necessary than ever and, besides mere subsistence agriculture, as Joseph Stiglitz puts it, all human activity depends on the respect of rules of conduct.

Is there a certain ratio between the size of a city and the wellbeing of its inhabitants and what is the role of political organization in the success of communal life?

Cities, and bigger cities for that sake, are very fragile environments. They apparently offer more comfort and shelter than the wild and yet the disruption of their services leaves people unable to survive by their own means. Order can be followed by chaos in a very short time and mere survival becomes difficult.

The theme, from a luddite perspective, has been recently explored by several books and movie pictures. And yet there is no sight of relenting in the trend toward larger population clusters.

As I prepared for this gathering of thinkers I reviewed some of the materials collected by The World Justice Project in its Rule of Law Index.

I was trying to find some patterns that would give us clues for the better management of cities.

The big survey, that already covers 79 countries and is representative of the perceptions of a huge chunk of the world’s population, compares countries within a region or an economic and development group.

The methodology applied allows some insight into the life of the cities, for the survey was applied in three of the most populous cities of each country.

Data from the Rule of Law Index shows considerable variation in the way people experience and perceive the rule of law around the world. This variation is higher when viewing the data at the country level where countries typically report similar rule of law results across their largest cities.

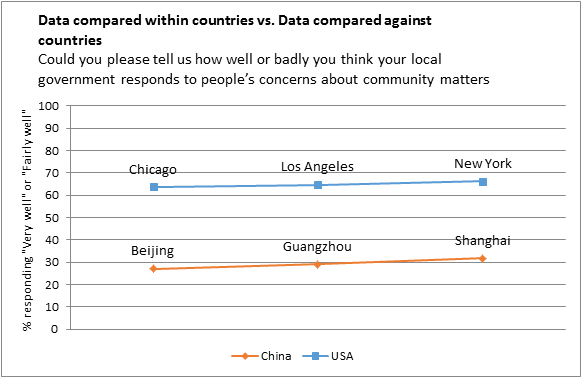

An illustrative case lies in comparing responses to one of the items of the questionnaire.

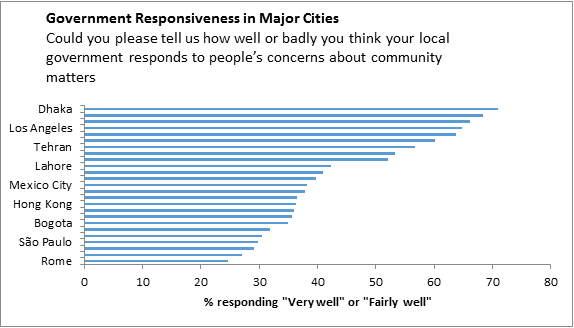

When asked “How well or badly does your local government respond to people’s concerns about community matters?” in China and the United States.

In China, responses vary from 27% of respondents in Beijing answering “very well” or “fairly well” to 32% in Shanghai.

In the US, on the other hand, the responses range from 64% in Chicago to 66% in New York City.

Clearly, we see that the differences between these two countries are greater than the differences within each country.

Nevertheless, variation exists at the city level as well. Respondents from Tokyo generally depict their city to strongly adhere to the rule of law, while respondents from Mexico City describe a situation in need of improvement.

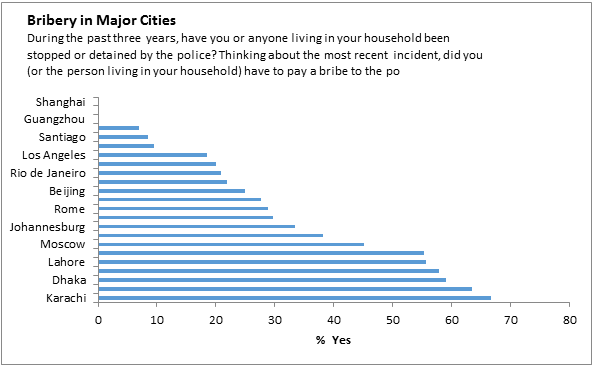

The following charts highlight a few of these concepts such as impunity, safety, the use of bribery, trust in public officials, and government responsiveness.

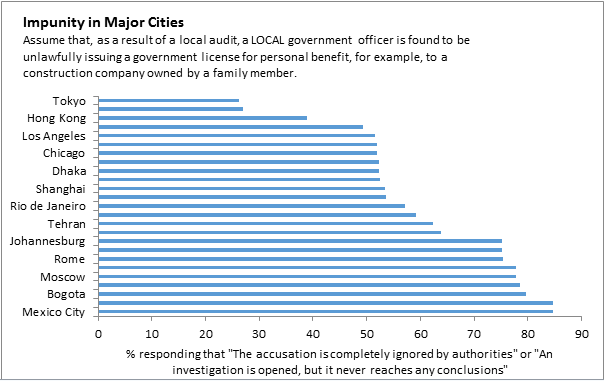

(1) To start, the perception of impunity exists in all major cities around the world. However these perceptions span a broad range:

From only 26% of respondents indicating that a local government official would not be held accountable for misdeeds in Tokyo to 85% of respondents indicating the same in Mexico City.

Latin American cities in particular stand out with high levels of perceived impunity. The demonstrations that began last June in Brazil called for better transportation, health care, and education conditions but, more consistently, they demanded the end of impunity for high ranking officials.

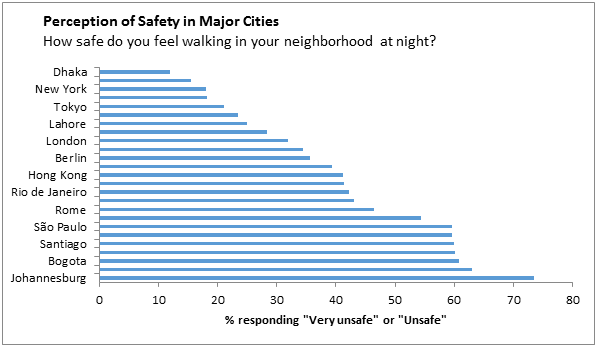

(2) Respondents in Johannesburg perceive their city to be highly unsafe with 73% of respondents replying that they feel “unsafe” or “very unsafe” when walking in their neighborhood at night.

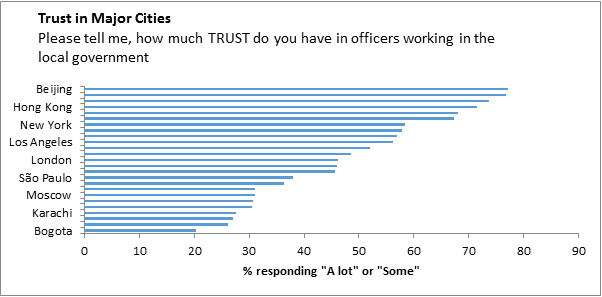

(3) East Asian cities have the highest levels of trust in their local government officials with Beijing, Guangzhou, Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Shanghai holding the top five positions among the major cities included in the sample.

(4) Bribery within the police seems to be a significant issue in much of the world with respondents in 7 of the largest 24 cities surveyed reporting that they, themselves, had to pay a bribe the most recent time they were stopped or detained by the police.

(5) Respondents in several of the largest cities of the world tend to see their local government as responsive to their needs. But this is not always the case. Only one in four respondents in Rome considered their local government to be responding “well” or “fairly well” to their concerns about community matters.

These few scattered examples well demonstrate that a good legal infrastructure and institution building are just as important as material infrastructure and GDP growth if we are to measure human progress.

***

This article was adapted from a speech delivered in October.

Photo Credit: Sao Paolo Skyline / Andre Deak