The world is no stranger to images of private opulence paid for with public money. The sprawling private residences and lavish compounds of deposed national leaders have become a common sight, showing there’s no shortage of corrupt leaders using government money for personal benefit—and getting away with it.

What we see in the media may be just the tip of the iceberg, however. New data suggests that consequence-free corruption is a widespread, corrosive force on governments around the globe.

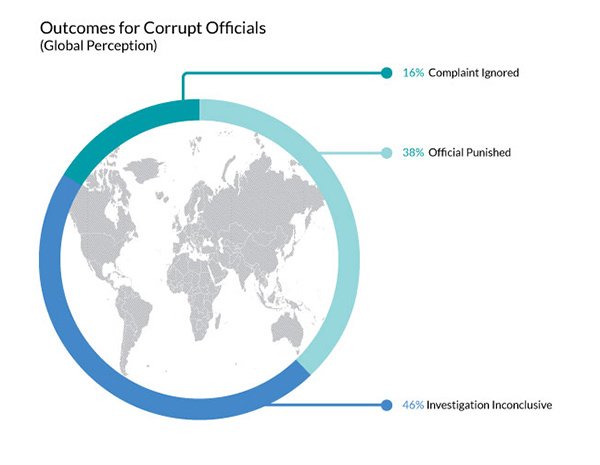

According to survey results from our 2014 World Justice Project Rule of Law Index, a majority of people—62 percent of individuals worldwide—believe that a high-ranking government officer guilty of using public money for personal benefit will face no punishment for their conduct.

While corruption hurts governments, impunity—the inability to root out corruption by punishing offenders—compounds the problem. Though almost all countries have laws against corruption, those laws are only effective if they are enforced: if offenders face reprimand and prospective offenders are deterred. Without that mechanism, corrupt practices are allowed to flourish, and public trust in government institutions declines.

Pessimistic global outlook on impunity

To measure impunity in corruption, our poll asked people in 99 countries what would happen when it is public knowledge that a government official is taking government money for private benefit.

Question:

“Assume a high-ranking government officer is taking government money for personal benefit. Also assume that one of his employees witnesses this conduct, reports it to the relevant authority, and provides sufficient evidence to prove it. Assume that the press obtains the information and publishes the story. Which one of the following outcomes is most likely?"

Respondents were given three outcomes: the official is punished; it is investigated but no conclusion is made; or the complaint is ignored entirely.

Together, the large majority of respondents said that the official would not be punished, even under the condition that evidence of wrongdoing is strong and the matter is in the press. Two-thirds of all countries had overall pessimistic outlooks on whether offenders would be held accountable.

Successes and failures to punish exists across regions

These results suggest a global distrust in accountability systems meant to maintain ethical government. Instead citizens across regions believe governments most often begin investigations in to complaints, only to let the culprit off.

Though there is relative similarity in responses across regions, there are also certainly standouts on both ends of the spectrum—and they’re geographically diverse. The top countries all poll with over 75% confidence that corruption will be punished, and hail from four different continents: Botswana (88%), New Zealand (79%), Norway (76%) and Hong Kong (75%). The worst performers—Uzbekistan (3%), El Salvador (11%), Argentina (17%), and Pakistan (17%)—hail from drastically different neighborhoods as well. Among region-wide differences, the rate of punishment stands out in one particular comparison: people in East Asia and Pacific are twice as likely as those in Latin America and the Caribbean to believe corrupt officials will be punished.

Poor and Middle Income Countries Perform the Same—Being the Richest Helps

There are many reasons to believe money will affect impunity. Poor countries have fewer resources to use to investigate, but perhaps incentives are greater to prosecute those wasting their limited wealth. Rich countries have well trained investigative officials, but leakages might be far less of a concern. When it comes to investigation—the most expensive process—citizen perceptions don’t corroborate these hypotheses: countries among all income levels investigate roughly the same amount.

It is the case, however, that punishment is perceived as significantly more likely in high income countries than in less wealthy countries (52% among high income, 33% among low income). There is nearly a twenty percent jump once a country is high-income: there is no difference among the punishment rates in low, low-middle, and upper-middle income, brackets. That means an upper-middle income country like Tunisia is as likely as low-income Tanzania to punish an offender (27%). What makes the highest-income countries markedly better at reprimanding is an important area for future research.

Local Officials As Unlikely to Face Consequences

Survey results also indicate that lower ranked officials are perceived to enjoy similar levels of impunity as high-ranking ones. On a survey question asking about a local government officer issuing a construction permit for personal benefit, 64% of global respondents responded that there would be no punishment.

Question:

"Assume that, as a result of an audit, a LOCAL government officer is found to be unlawfully issuing a government license for personal benefit, for example, to a construction company owned by a family member. Which one of the following outcomes is most likely?"

The key finding here is not that local officials are slightly less likely to be punished than high ranking ones in most regions: it’s that both local and national officials enjoy high levels of impunity. That result both seems to mitigate the effect of the press in bringing justice (present only in question 1), and undercuts the idea that local officials will be much easier to prosecute given lower political clout.

Either way, according to this data people have as little faith that dispersed, common instances of corruption will be punished as high-profile and visible ones.

Methodological note: Data presented here is taken from surveys conducted as part of the General Population Poll (GPP), one component of the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2014. The GPP questionnaire includes 87 perception-based questions and 56 experience- based questions, along with socio-demographic information on all respondents. The questionnaire is translated into local languages, adapted to common expressions, and administered by leading local polling companies using a probability sample of 1,000 respondents in the three largest cities of each country. Depending on the particular situation of each country, three different polling methodologies are used: Face-to-face, Telephone, or Online. The GPPs are carried out in each country every other year.