This is part two of a four-part series on how access to justice build resilience in the Sahel. Read the introduction here.

Senegal: A Nation of Contrasts

Most visitors to West Africa enter through Senegal, a regional hub for European tourists and business travelers alike. With uncertainty descending upon travelers worldwide, it was comforting to know my port of entry would honor a U.S. passport without visa restrictions. Even so, I was aware that this special relationship has deep and tangled roots in the middle passage: Senegal's status as a regional transit hub dates back to its history as a colonial entrepôt and a major node in the transatlantic slave trade.

As I arrived in the capital, Dakar, I mused about how the pandemic has temporarily thrown this history into relief, upending simple narratives about poverty and contagion, vulnerability and disease, development and foreign aid. Whereas thousands of Africans had been forcibly carried to America by way of Gorée Island, the historic slave fort situated three kilometers off the coast of Dakar, I would be privileged to do the journey in reverse, as a guest, carrying no burden but curiosity. I hoped my COVID precautions were enough to prevent an equally invisible stowaway.

Senegal provides a dramatic introduction to West Africa's many contradictions. Take the Blaise Diagne International Airport, for instance: a gleaming new compound situated far from the prosperous coast, it is a symbol of Dakar's regional status as the economic pacesetter. Named for a former mayor, the first black African elected to the French Chamber of Deputies, it is also a symbol of colonial assimilation.

Blaise Diagne was constructed to replace Leopold Sedar Senghor, a cramped and aging facility pinched into the suburbs of Dakar. A $575 million contract to develop the new airport was awarded to the Saudi Binladen Group (SBG), an international conglomerate with a deep portfolio of megastructures erected in arid spaces. After numerous delays and nearly ten years of construction, Blaise Diagne now sits on a vast patch of red clay land, towering over the dusty village nearby. Its remote location, 45 kilometers outside the city, is meant to leave plenty of room for expansion as well as to spur investment in the surrounding community. When I arrived, however, both the new airport and its surrounding countryside remained sleepy. Bleary locals lay sprawled across their luggage, awaiting an early morning flight. Outside, in the summer heat, a taxi-man dozed in his car.

Wandering around the terminal at night, I wondered at the net value of such a large infrastructure project in a context of competing development priorities. How should policymakers weigh the potential for rapid economic growth, often funded through securitized debt obligations, against other priorities for security and resilience? How much justice could a government supply, for example, for $575 million? For now, the answer to these questions remains deferred, awaiting the end of a global pandemic, a break in the regional conflict, and the return of tourist flows.

A planned train connection to Dakar is not yet complete, so I waited until dawn to catch a taxi into the city: Senegal is quite safe, friends who know such things had told me, but one must avoid traveling anywhere after dark. As the sun began to rise, we passed dusty fields and donkeys staring sheepishly at the traffic. In a nearby village, children stared from vacant windows or ran barefoot down unimproved roads. As we approached Dakar, however, the first thing I noticed was endless construction; the second was an immense crowd, dusty and hot, living and working amidst the peremptory neighborhoods that ring the city center. In many areas, half-built structures dwarfed the finished buildings. The whole landscape felt provisional, like a question posed to the desert. It was as if some maniacal sculptor had chosen to recreate a scene of aerial bombardment — peaks and craters of concrete and rebar, here and there a house intact, throngs of women and children carrying bundles — only in reverse, with everyone bustling and building everywhere at once.1

Yet the signs of effective governance are also apparent in Senegal. A modern highway system, complete with tollbooths employing ticket-workers to speed the flow of traffic, connects the city with its outlying suburbs. Well-marked taxis queue patiently at airports and hotels, while crowded mini-buses provide inexpensive transportation for the poor. Dakar's grocers may lack some of the opulence and variety of a supermarket, but their air-conditioned shops are tidy and well supplied with essentials. Peddlers and SIM-card hawkers line the busy streets, while children in brightly colored uniforms laugh on their way home from school.

Senegal has also taken a firm but considered approach to preventing the spread of COVID-19. Despite having just a handful of confirmed cases at the time, health authorities quickly expanded testing and closed public spaces such as restaurants and nightclubs; health authorities were forthcoming about early outbreaks, and they provided solid guidance to citizens at risk of contracting the virus. At my hotel, a decidedly two-star establishment, the staff were equipped with gloves and an infrared thermometer. While such measures are of limited effectiveness in containing the spread of coronavirus, they do speak to the government's ability to issue trusted guidance in a timely manner.

Thus far, Senegal has largely been spared the ethnic and religious conflicts that have devastated its neighbors across the Sahel. Yet is effective governance more the cause or an effect of this relative peace and prosperity? It is a difficult question to separate from the confounding variables of history. But the underlying correlation between good governance, economic development, and reduced violence is well established: ultimately, peace allows effective institutions to flourish even as these institutions work to defuse civil conflict.2

How then might better governance translate into improvements in security?

When I asked this question of a taxi-man, he replied, "We Senegalese treat each other with respect no matter what. There is corruption and problems in the government; but without respect, we have nothing. Nobody taught us how to live in peace; it is something we teach ourselves."

I find this answer insightful. It reflects the West African culture of self-help, as well as the meaningful work that Senegal has done to address poverty since the 1990's.3 Such incremental advances have strengthened order and security. A fairer society helps to strengthen the social contract, and political scientists have found a strong correlation between equality of opportunity and social trust.4 Equality also reinforces the culture of consensus that my research subjects emphasized. Together, this sense of trust and the feeling of empowerment it engenders have sustained an ethos of toleration, an attitude grounded in respect for differences, which has lent the Senegalese greater patience in their country's march toward justice.

These values also reflect Senegalese efforts to make civil justice more accessible for all.

One effective government program has established "justice houses" or maisons de justice, which embed essential government services within the local community. Administered by the Ministère de la Justice with support from the Embassy of France and the Open Society Initiative West Africa (OSIWA), these semi-formal courts provide mediation and conciliation services in accordance with local customs and usages.

For example, one respondent cited the maison de justice in Ndangalma, a rural village in the Diourbel region of western Senegal, for its success in resolving conflits fonciers (land disputes) which lie at the heart of much inter-communal conflict in the Sahel. The maisons de justice handle civil matters as well as simple offenses, resolving cases such as debt recovery, land matters, and neighborhood conflicts; as well as disputes within the family, between renter and proprietor, or among the parties of a small service contract. They also function as a one-stop shop for legal information, providing help with administrative justice and redress for grievances. The maisons de justice therefore provide the physical infrastructure for a broader strategy, known as justice de proximité, which aims to help Senegalese citizens navigate problems of inheritance, divorce, marriage, civil status, registration of economic cooperatives and nonprofit associations, protection of vulnerable persons, property transactions, official complaints, provisional detention, labor contracts, and maintenance obligations.5

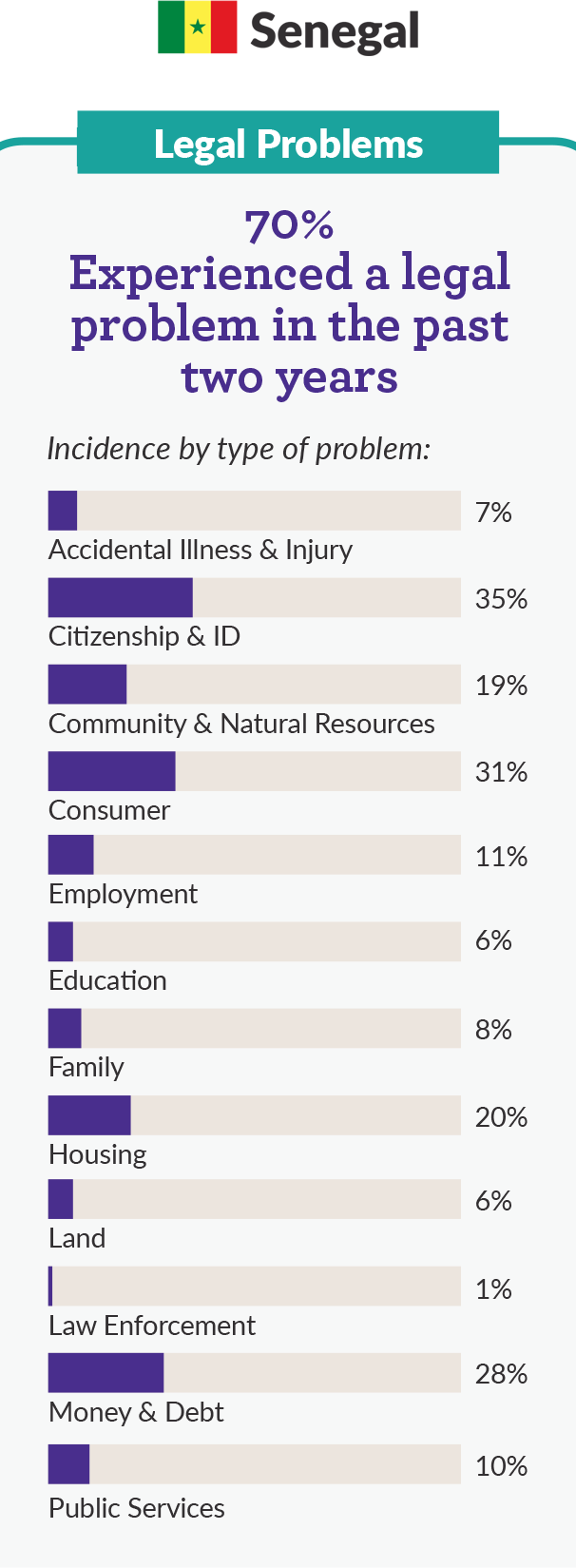

Yet such devolution of power to local authorities can provide meaningful access to justice only insofar as local norms correspond with universal principles of human rights. In this respect, the problem of civil justice in the Sahel is a question of how far and for how long the law will accommodate local variance in the treatment of women and other vulnerable groups. Thus, an equally significant component of justice reform are the grassroots organizations working to change attitudes and practices on the ground.

An exemplary program is the project to end female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage, conducted by the non-governmental organization Réseau Siggil Jigéen, which paired leadership training and network-building activities with the production and dissemination of materials intended to inform and persuade the public. This project, supported by UNICEF, used radio, film, and print materials to sensitize local audiences to the laws and conventions against child marriage and FGM — including materials in French, Wolof, Diola, Mandingo, Soninke, Serer, and Pulaar. In addition, it enlisted the support of security agents and gendarmes, as well as establishing "clubs de jeunes filles" (girls clubs) in the local schools. It has been effective in creating movement at the grassroots level because it leveraged the international human rights framework — in this case, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child — in order to empower and awaken local communities to demand protection from the state.

Like much of the Sahel, Senegal remains suspended between its past and its future. Looking backwards, its justice ministers are finding ways to dissolve a colonial legacy marked by structural expropriation and the rigidity and centralization of a French civil code. Looking forward, its people are searching for ways to claim their right to equality under the law without disrupting a delicate balance between local customs and a commitment to laïcité — the secular notion, imported from France, that separation of church and state requires a clear distinction between private life and the public sphere. The effort to harmonize these goals will be a long-term endeavor, but the Senegalese are intent on leading the way.

1 The economist Paul Collier attributes this haphazard pattern of development to an injurious poverty trap. The poor often lack the means to finance a construction project from start to finish, Collier notes, even as their environment makes it difficult to save. Investing time and material into a house therefore imposes powerful discipline upon the poor, since the financial penalties for liquidating these raw materials is so painful.

Unfortunately, this crude form of banking is also terribly inefficient, since a single finished house is of much greater use to the poor than are ten concrete shells without a roof.

2 For an overview of the longitudinal data, see the World Bank Group, World Development Report 2017, Ch 4. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25880/9781464809507_Ch04.pdf

3 See "Inequalities in the Context of Structural Transformation: The case of Senegal": http://africainequalities.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Senegal-Country-Study.pdf

4 Rothstein, B., & Uslaner, E. (2005). All for All: Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. World Politics, 58(1), 41-72. doi:10.1353/wp.2006.0022. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/world-politics/article/all-for-all-equality-corruption-and-social-trust/09B64F404EB0F753E78680B70A9ABEDB

5 In Senegal, l'obligation alimentaire refers to a specific obligation, whether customary or defined by law, to provide food or other essential support to another person in need.

Support for "Access to Civil Justice in the Sahel" has been provided by the Knowledge Management Fund, a program of the Knowledge Platform Security & the Rule of Law at the Clingendael Institute for International Relations, Netherlands.